Bayesian Clustering

Apr 08, 2025

Learning Objectives

- We will introduce the basic mixture modeling framework as a mechanism for model-based clustering and describe computational and inferential challenges.

- Variations of the popular finite Gaussian mixture model (GMM) will be introduced to cluster patients according to ED length-of-stay.

- We present an implementation of mixture modeling in Stan and discuss challenges therein.

- Finally, various posterior summaries will be explored.

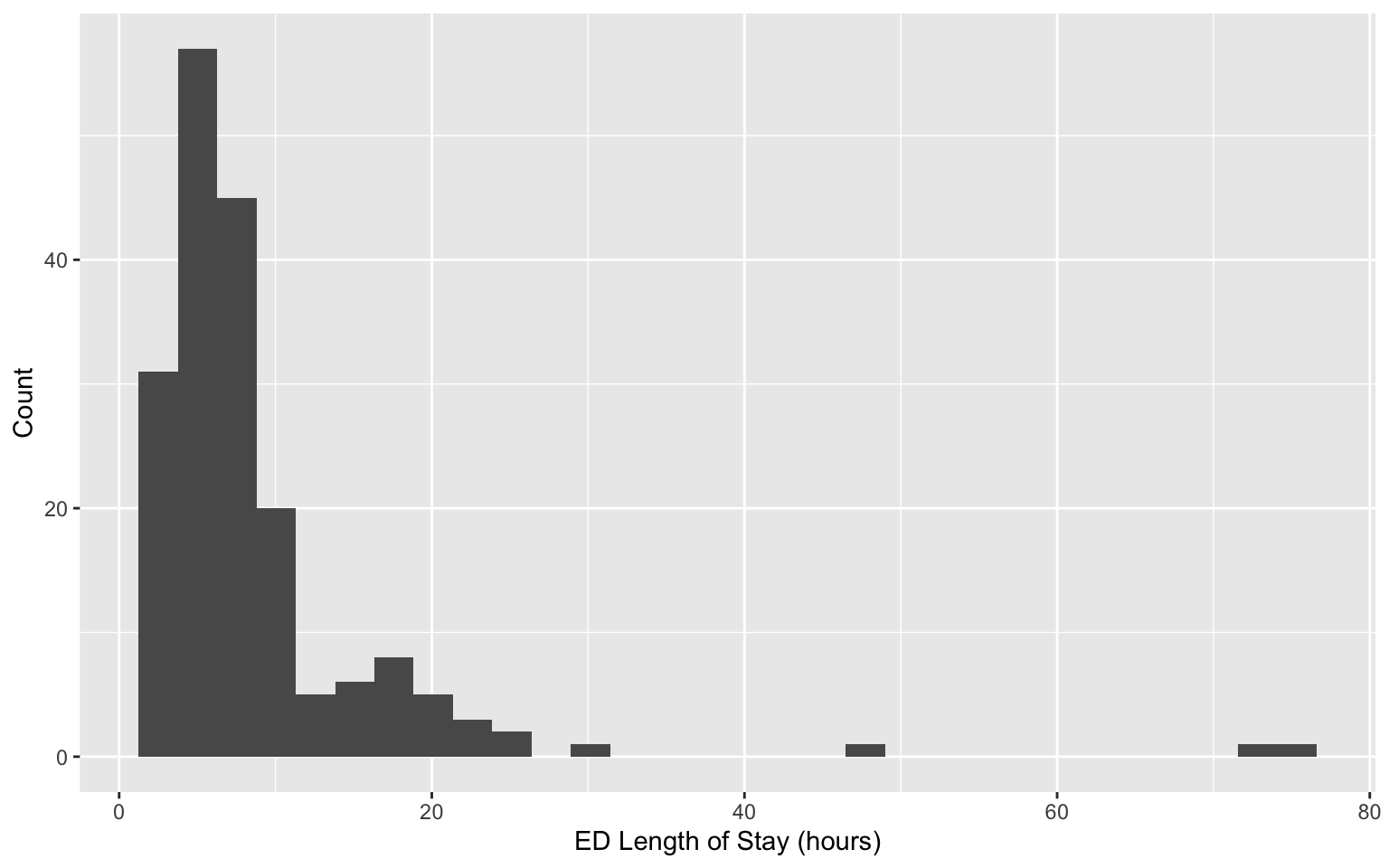

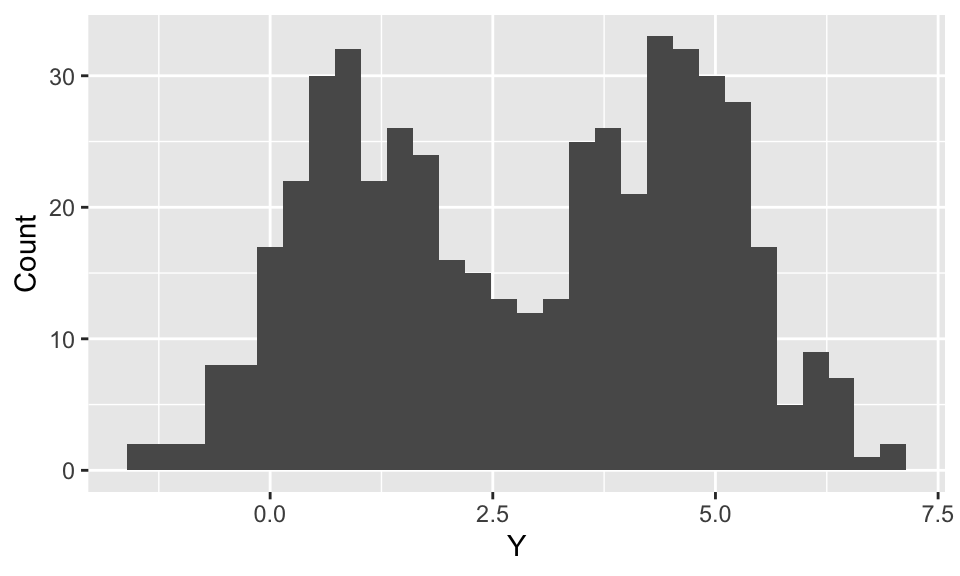

Finding subtypes

Revisiting data on patients admitted to the emergency department (ED) from the MIMIC-IV-ED demo.

Can we identify subgroups within this population?

The usual setup

Most models introduced in this course are of the form:

The usual setup

Linear regression:

Binary classification:

Limitations of the usual setup

Suppose patients

Limitations of the usual setup

Limitations of the usual setup

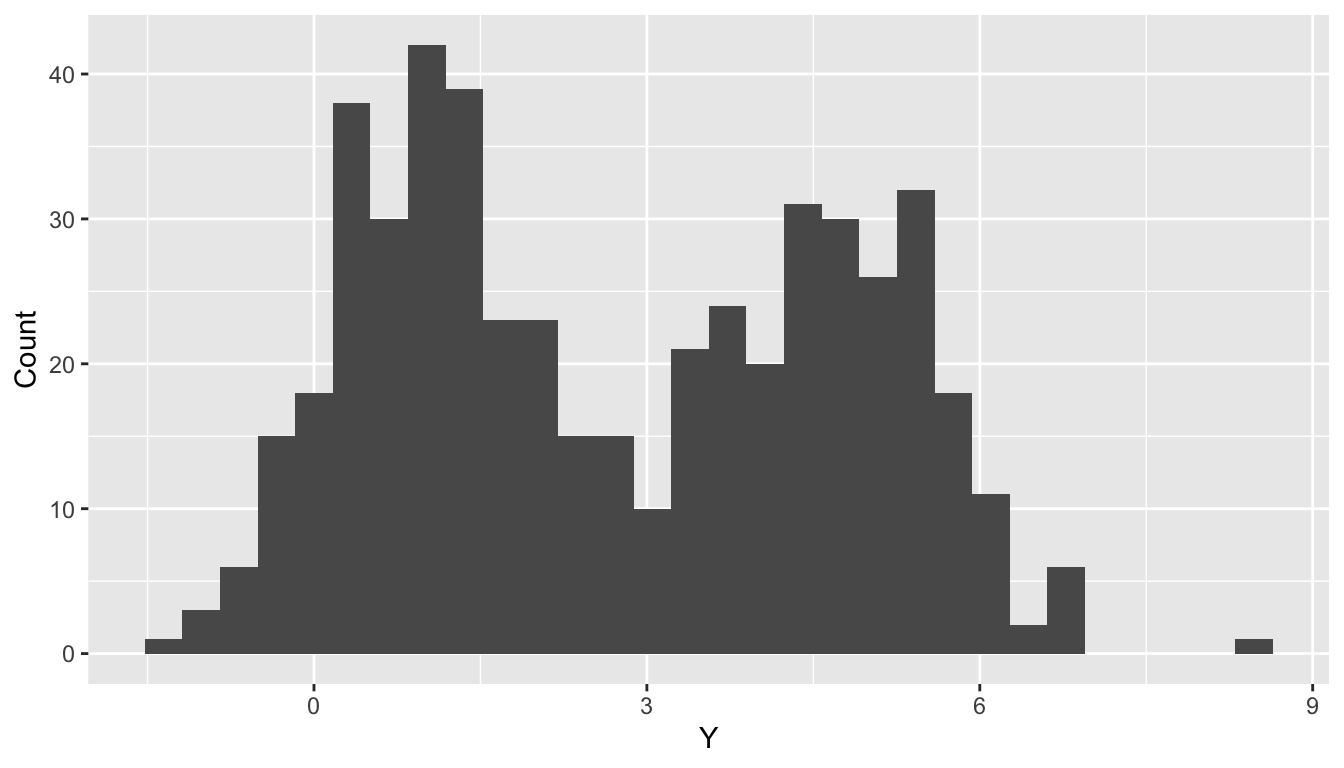

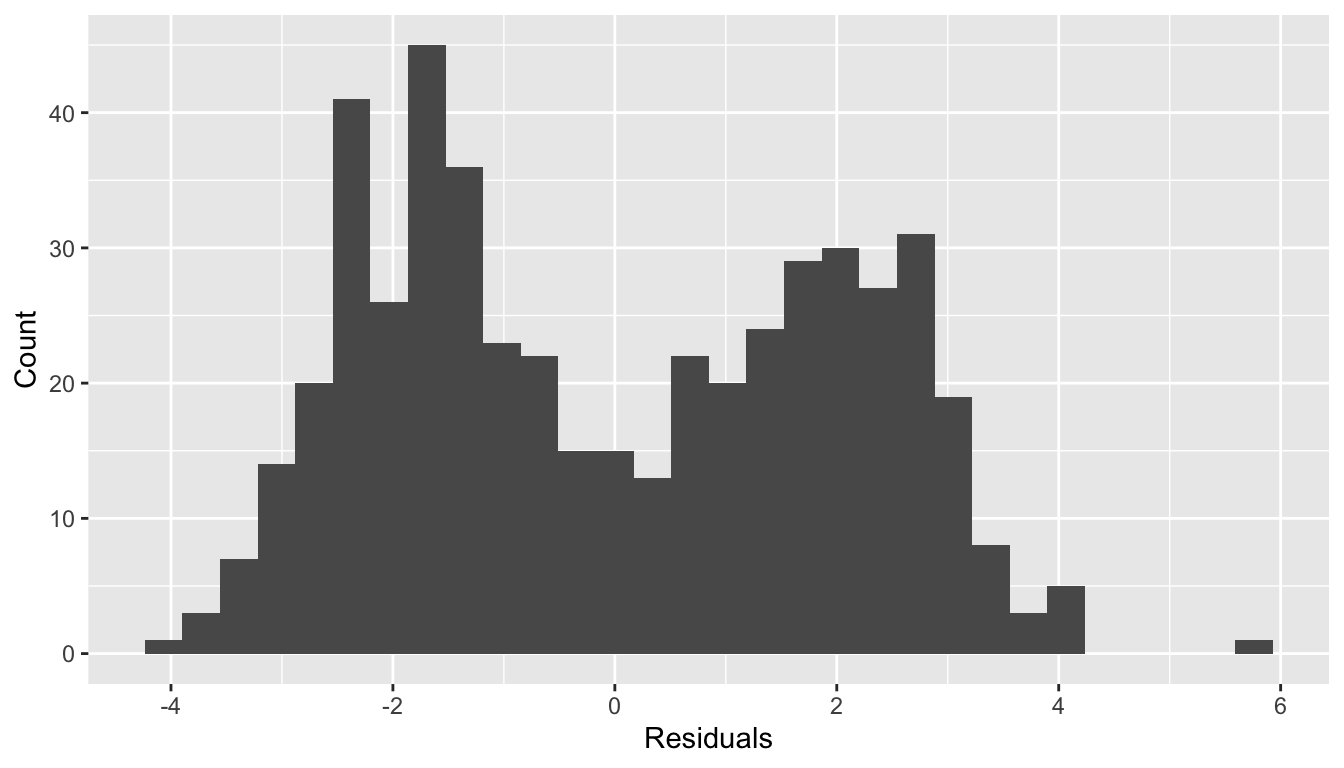

Normality of residuals?

Mixture Model

Motivation for using a mixture model: Standard distributional families are not sufficiently expressive.

- The inflexibility of the model may be due to unobserved heterogeneity (e.g., unrecorded treatment history).

Generically,

Uses of mixture models:

- Modeling weird densities/distributions (e.g., bimodal).

- Learning latent groups/clusters.

Mixture Model

This mixture is comprised of

When

It is common to let,

- The component densities share a functional form and differ in their parameters.

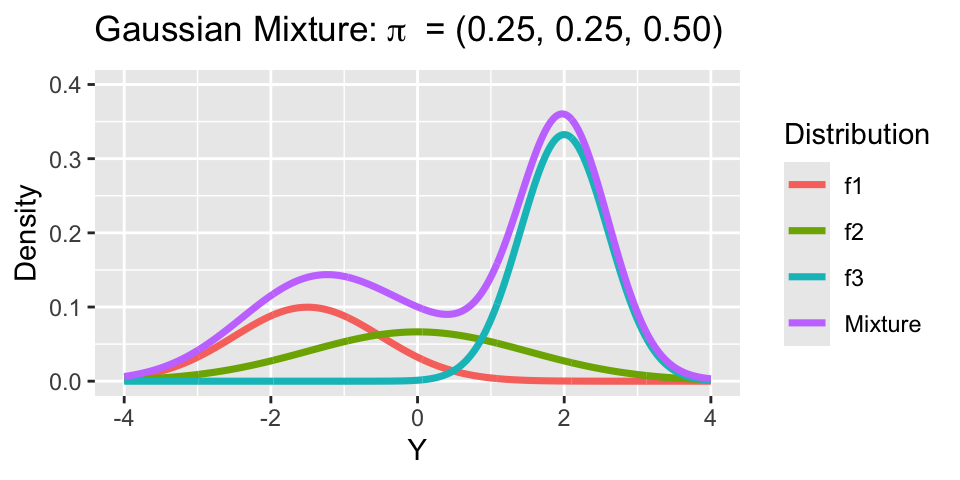

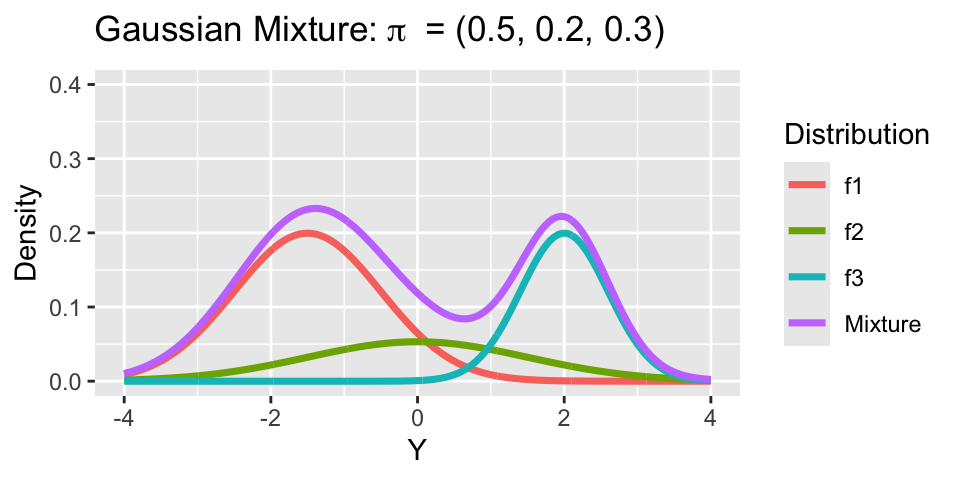

Gaussian Mixture Model

Letting

For multivariate outcomes

Gaussian Mixture Model

Consider a mixture model with 3 groups:

- Mixture 1:

- Mixture 2:

- Mixture 3:

Notice, both means

Generative perspective on GMM

To simulate from a

- Sample the component indicator

- Given

Generative perspective on GMM

This is essentially the code used to simulate the missing treatment history example.

Marginalizing Component Indicators

The label

But

This is key to implementing in Stan.

Gaussian mixture in Stan

Component indicators Stan. As before, suppose

The log-likelihood is:

log_sum_exp is a Stan function.

Gaussian mixture in Stan

// saved in mixture1.stan

data {

int<lower = 1> k; // number of mixture components

int<lower = 1> n; // number of data points

array[n] real Y; // observations

}

parameters {

simplex[k] pi; // mixing proportions

ordered[k] mu; // means of the mixture components

vector<lower=0>[k] sigma; // sds of the mixture components

}

model {

target += normal_lpdf(mu |0.0, 10.0);

target += exponential_lpdf(sigma | 1.0);

vector[k] log_probs = log(pi);

for (i in 1:n){

vector[k] lps = log_probs;

for (h in 1:k){

lps[h] += normal_lpdf(Y[i] | mu[h], sigma[h]);

}

target += log_sum_exp(lps);

}

}Of note: simplex and ordered types.

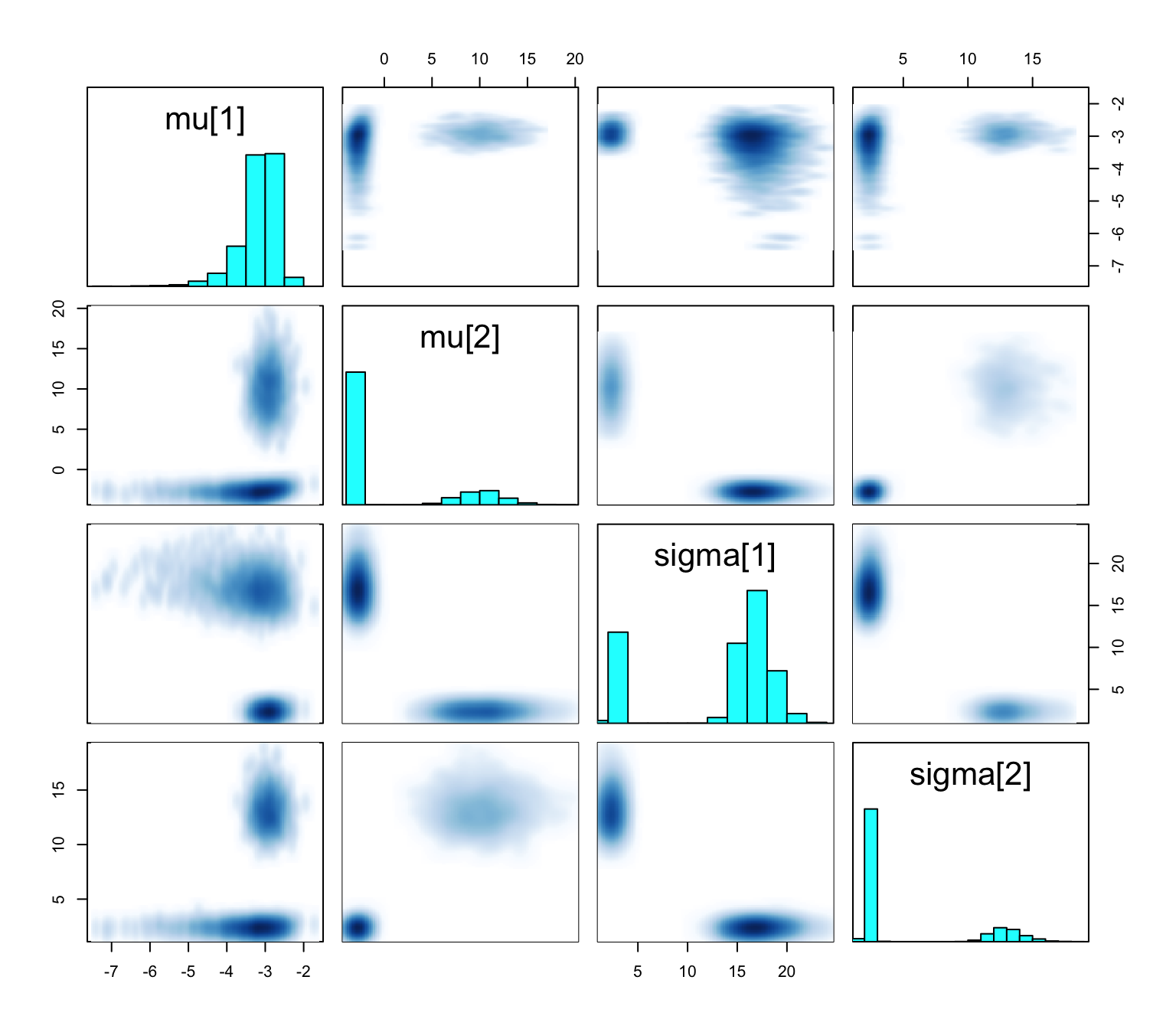

First fit

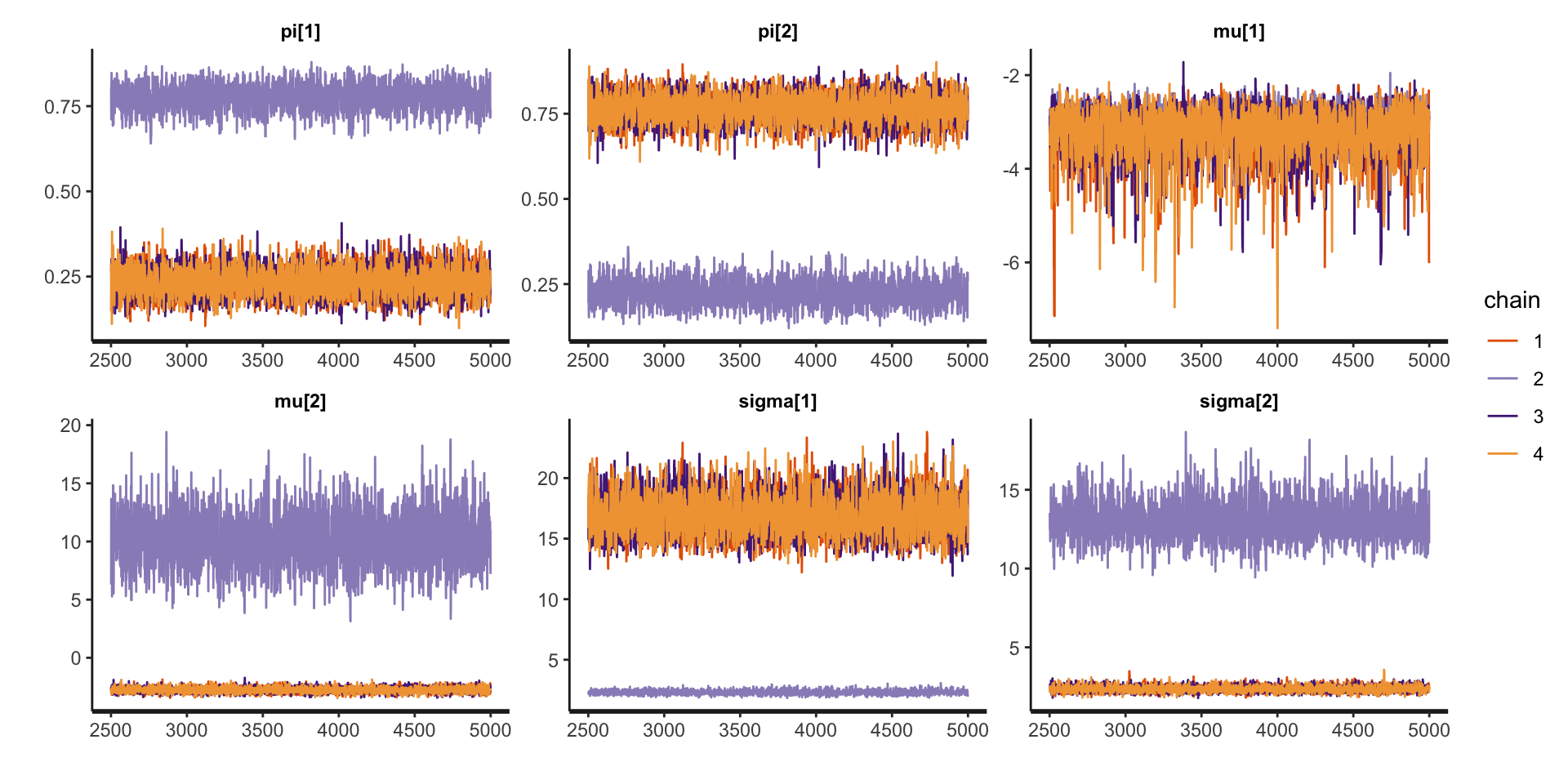

Inference for Stan model: anon_model.

4 chains, each with iter=5000; warmup=2500; thin=1;

post-warmup draws per chain=2500, total post-warmup draws=10000.

mean se_mean sd 2.5% 97.5% n_eff Rhat

pi[1] 0.37 0.17 0.24 0.16 0.83 2 6.35

pi[2] 0.63 0.17 0.24 0.17 0.84 2 6.35

mu[1] -3.17 0.09 0.51 -4.49 -2.49 33 1.05

mu[2] 0.45 3.96 5.69 -3.17 13.08 2 5.14

sigma[1] 13.25 4.48 6.46 2.09 20.11 2 4.97

sigma[2] 5.03 3.28 4.68 2.03 14.78 2 7.56

Samples were drawn using NUTS(diag_e) at Sat Mar 22 13:54:38 2025.

For each parameter, n_eff is a crude measure of effective sample size,

and Rhat is the potential scale reduction factor on split chains (at

convergence, Rhat=1).What is going on?

Bimodal posterior

- In one mode,

Bimodal posterior

The Gaussian clusters have light tails, so outlying values of

Things to consider when your mixture model is mixed up

Mixture modeling, especially when clusters are of interest, can be fickle.

- Different mixtures can give similar fit to data, leading to multimodal posteriors that are difficult to sample from (previous slides).

- Clusters will depend on your choice of

- Increasing

Things to consider when your mixture model is mixed up

- Employ informative priors.

- Vary the number of clusters.

- Change the form of the kernel.

Updated model

// saved in mixture2.stan

data {

int<lower = 1> k; // number of mixture components

int<lower = 1> n; // number of data points

array[n] real Y; // observations

}

parameters {

simplex[k] pi; // mixing proportions

ordered[k] mu; // means of the mixture components

vector<lower = 0>[k] sigma; // sds of the mixture components

vector<lower = 1>[k] nu;

}

model {

target += normal_lpdf(mu | 0.0, 10.0);

target += normal_lpdf(sigma | 2.0, 0.5);

target += gamma_lpdf(nu | 5.0, 0.5);

vector[k] log_probs = log(pi);

for (i in 1:n){

vector[k] lps = log_probs;

for (h in 1:k){

lps[h] += student_t_lpdf(Y[i] | nu[h], mu[h], sigma[h]);

}

target += log_sum_exp(lps);

}

}- Informative prior on

- Mixture of Student-t.

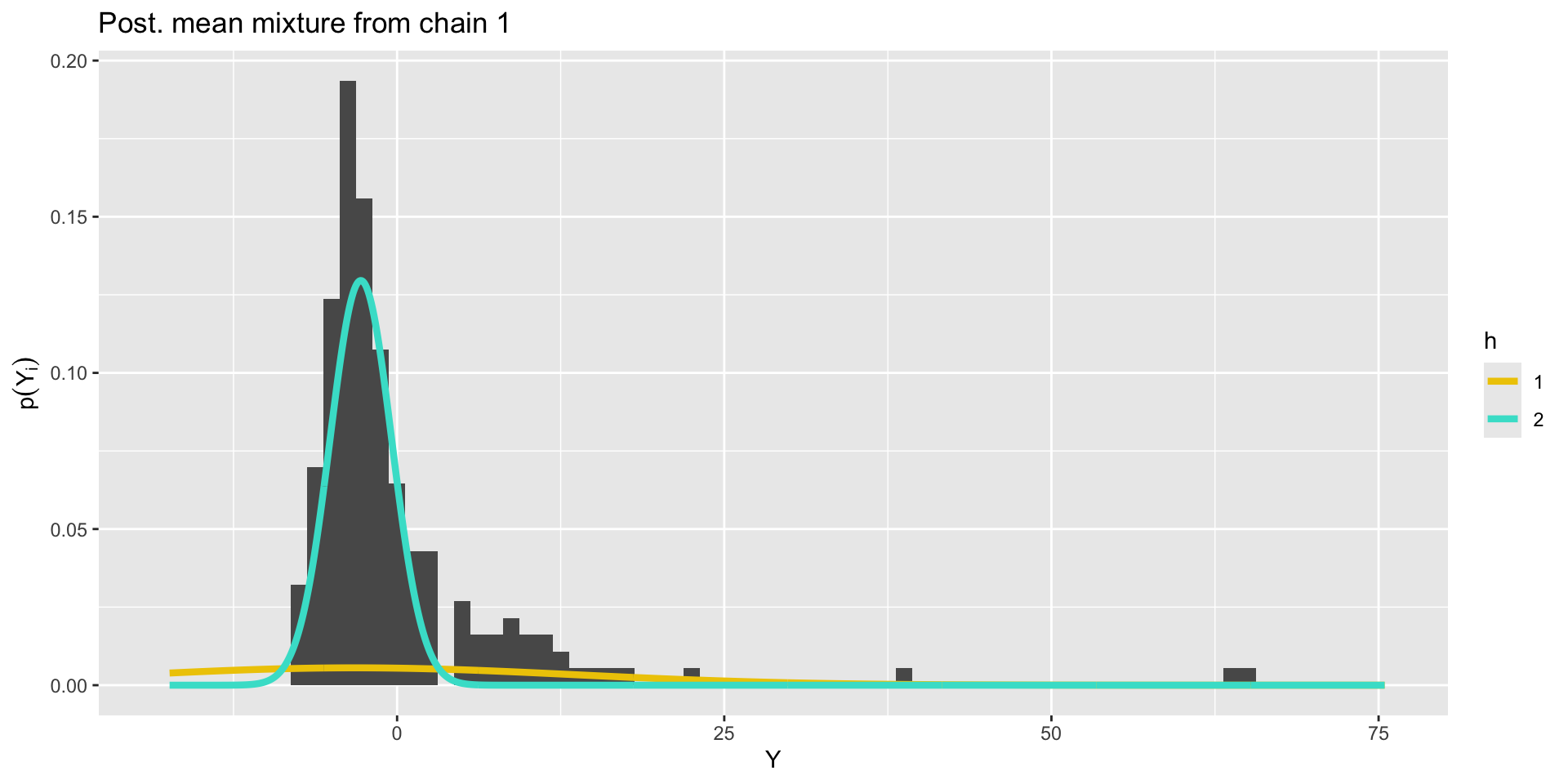

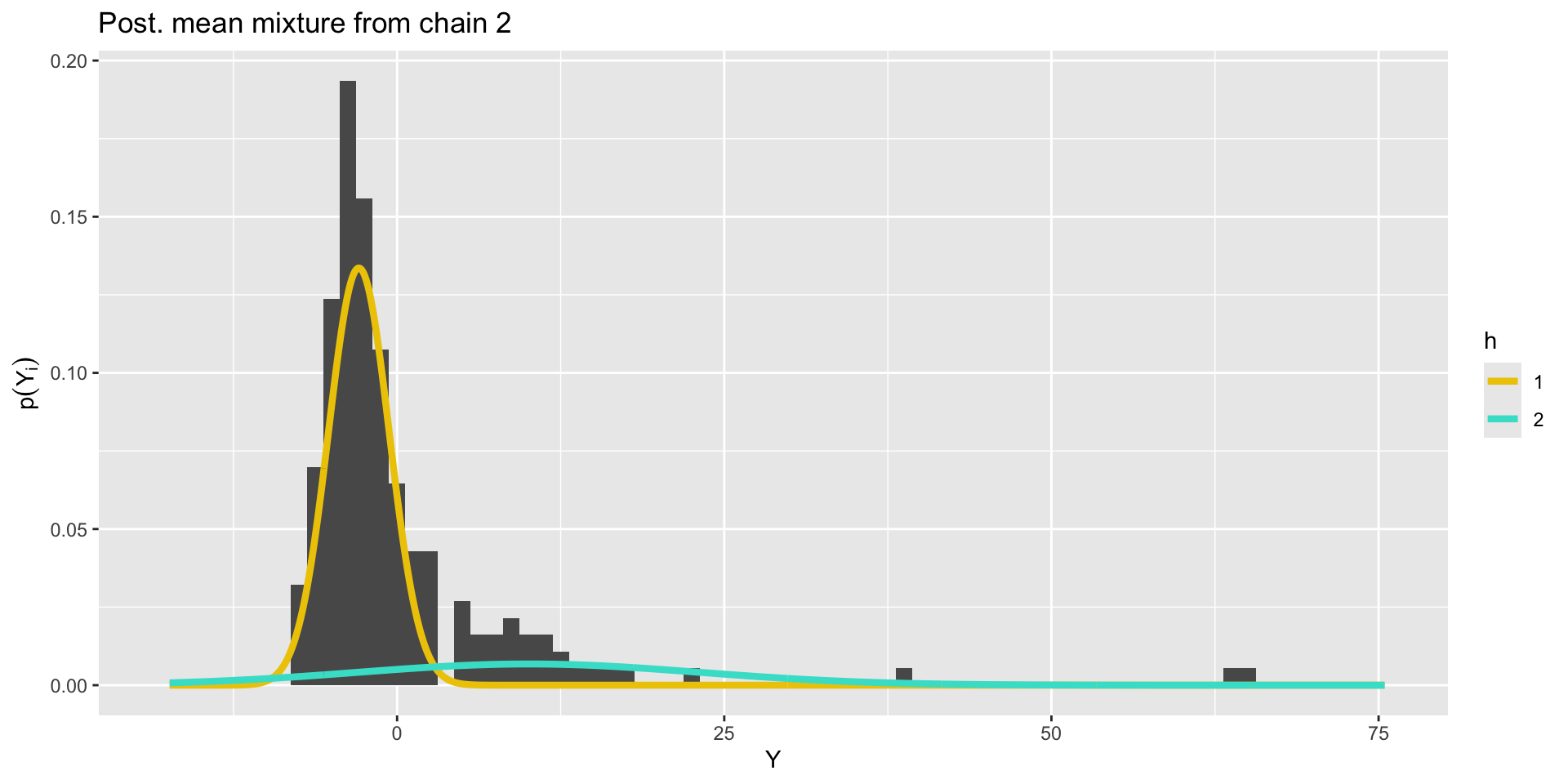

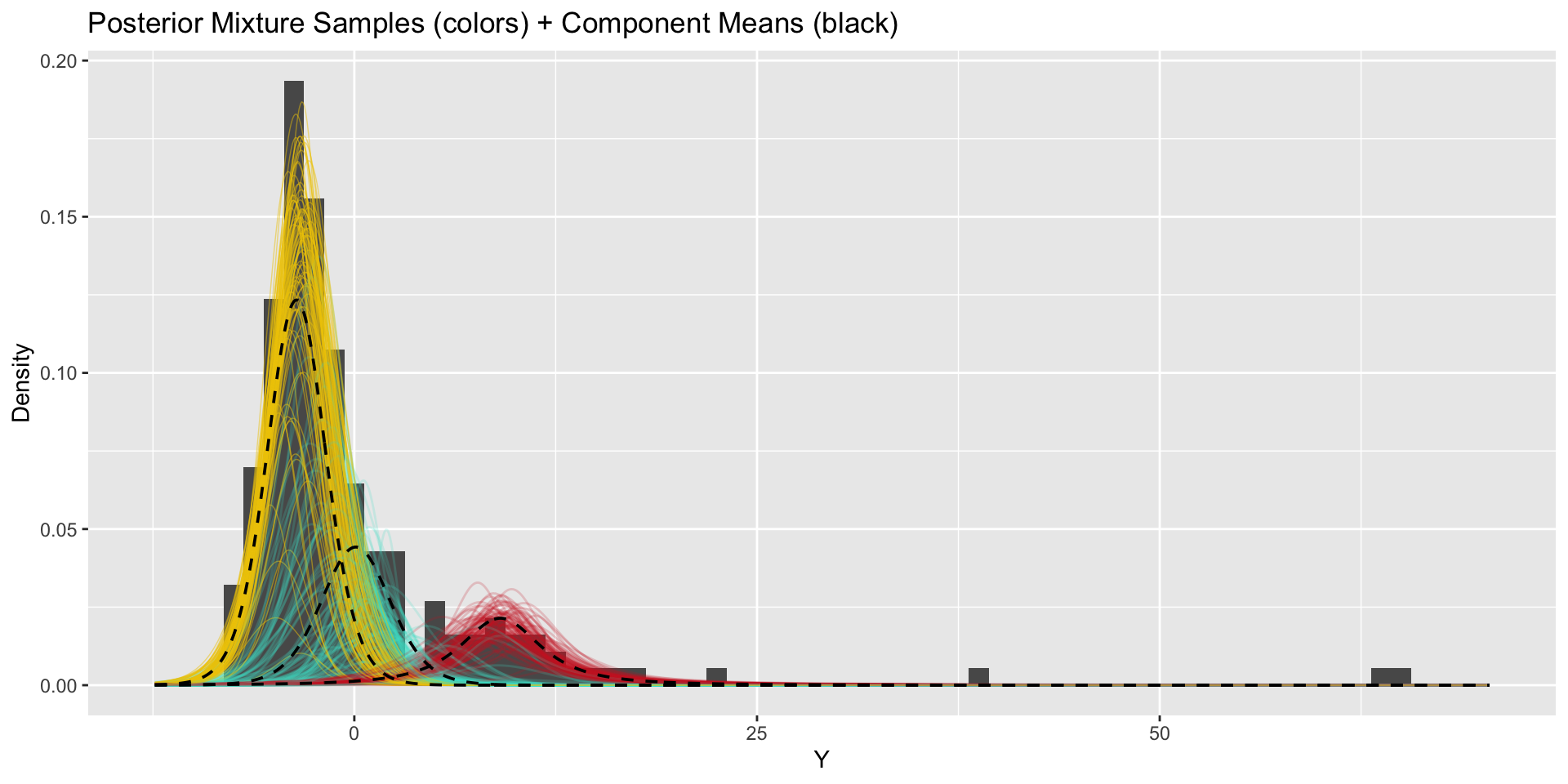

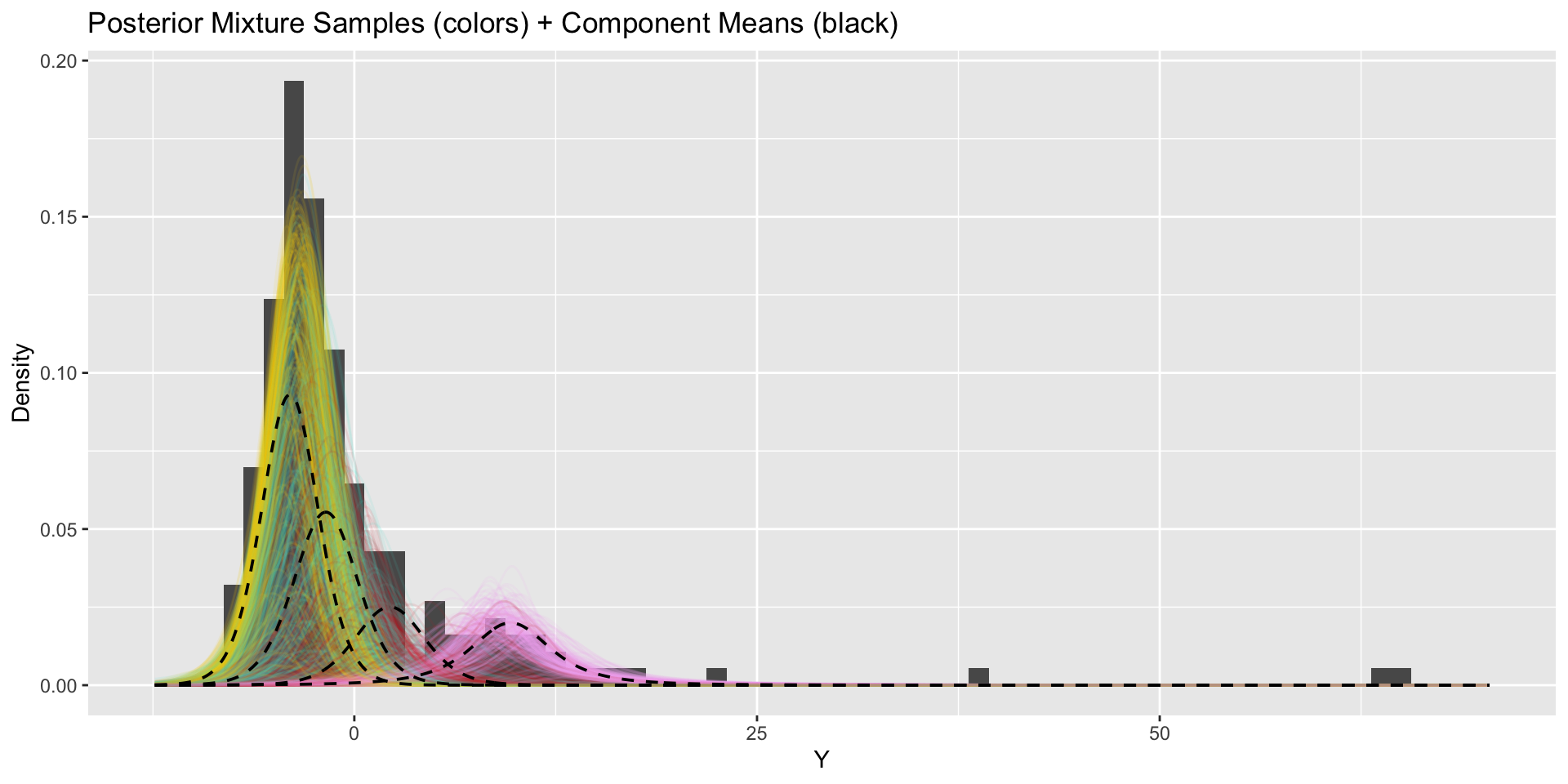

Updated model fit

Inference for Stan model: anon_model.

4 chains, each with iter=5000; warmup=2500; thin=1;

post-warmup draws per chain=2500, total post-warmup draws=10000.

mean se_mean sd 2.5% 25% 50% 75% 97.5% n_eff Rhat

pi[1] 0.81 0.00 0.04 0.73 0.79 0.81 0.83 0.87 5567 1

pi[2] 0.19 0.00 0.04 0.13 0.17 0.19 0.21 0.27 5567 1

mu[1] -2.96 0.00 0.22 -3.39 -3.10 -2.96 -2.81 -2.53 7318 1

mu[2] 8.30 0.02 1.10 6.03 7.66 8.35 9.01 10.28 4306 1

sigma[1] 2.20 0.00 0.17 1.88 2.09 2.20 2.31 2.55 5987 1

sigma[2] 2.82 0.00 0.40 2.06 2.55 2.81 3.09 3.64 6745 1

nu[1] 11.98 0.04 4.44 5.14 8.75 11.38 14.57 22.22 9860 1

nu[2] 1.54 0.00 0.43 1.03 1.25 1.46 1.74 2.50 9286 1

Samples were drawn using NUTS(diag_e) at Sat Mar 29 12:52:38 2025.

For each parameter, n_eff is a crude measure of effective sample size,

and Rhat is the potential scale reduction factor on split chains (at

convergence, Rhat=1).Updated model results

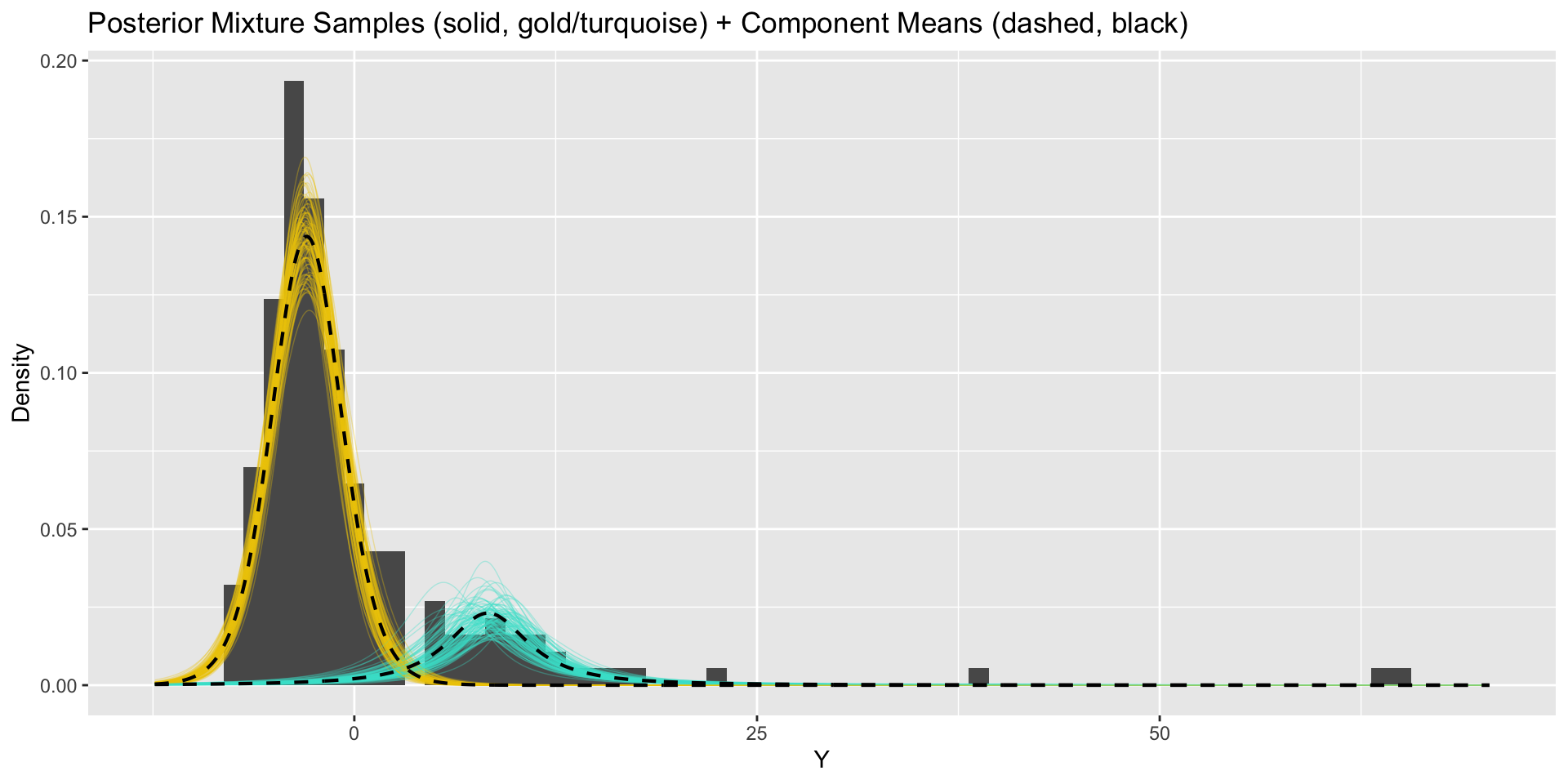

From marginal mixture model to clusters

Stan cannot directly infer categorical component indicators

Given these cluster membership probabilities, we can recover cluster indicators through simulation:

From marginal mixture model to clusters

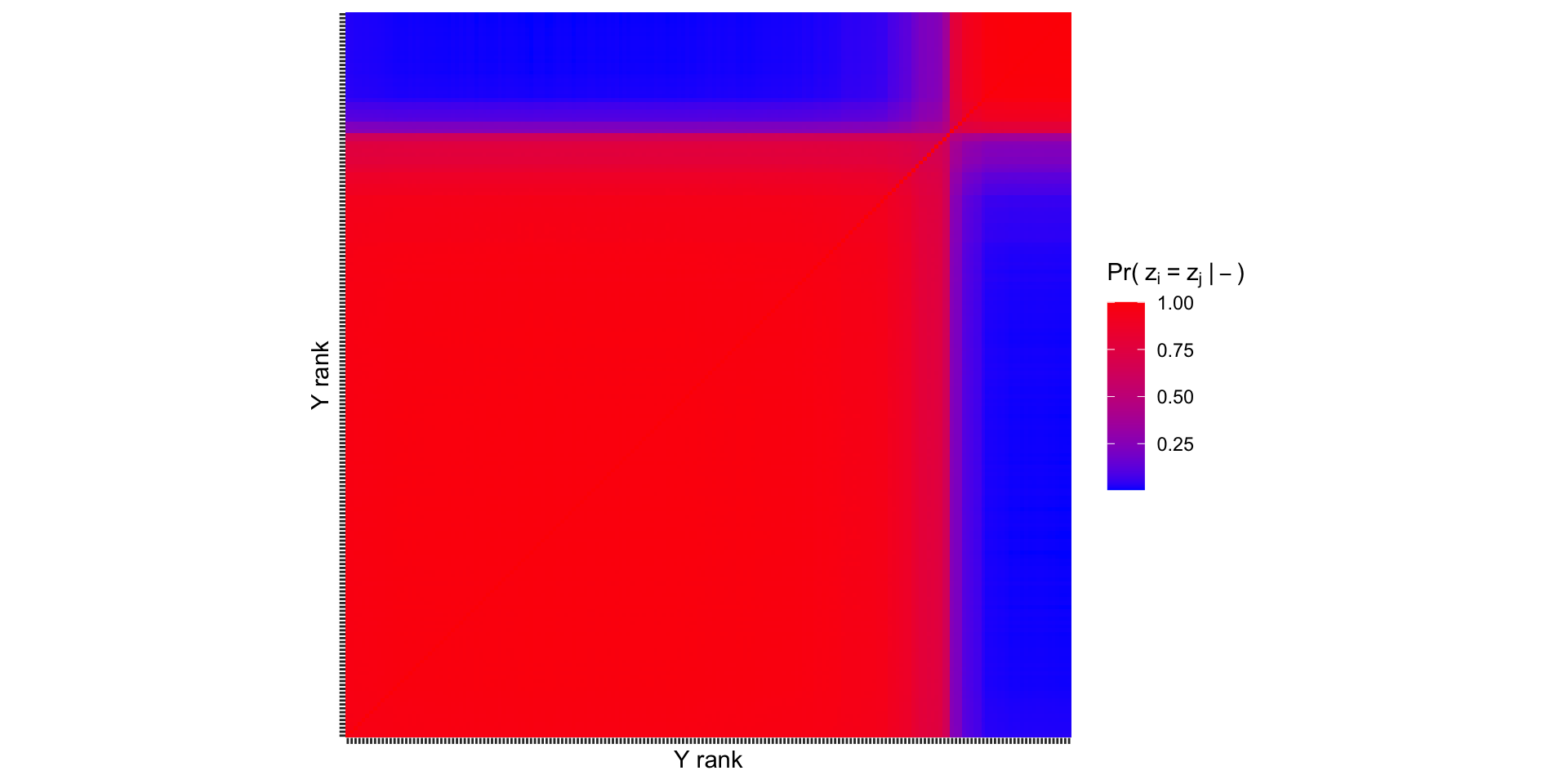

Co-clustering probabilities

Recovering

It is common to arrange these probabilities in a co-clustering matrix

Co-clustering probabilities

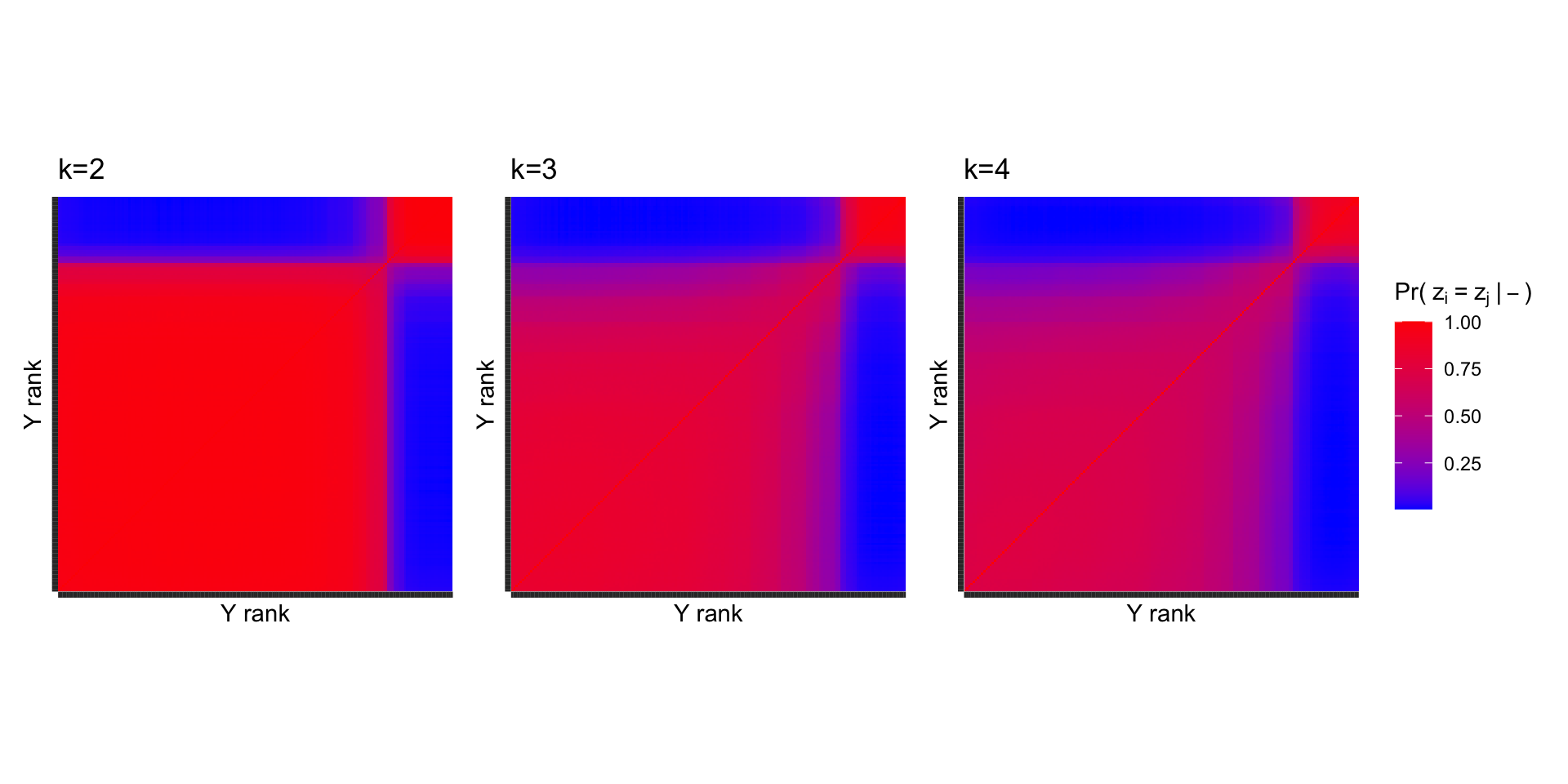

How do our results change when we use more components?

How do our results change when we use more components?

Co-clusterings across

The same general pattern persists when more clusters are used, indicating that

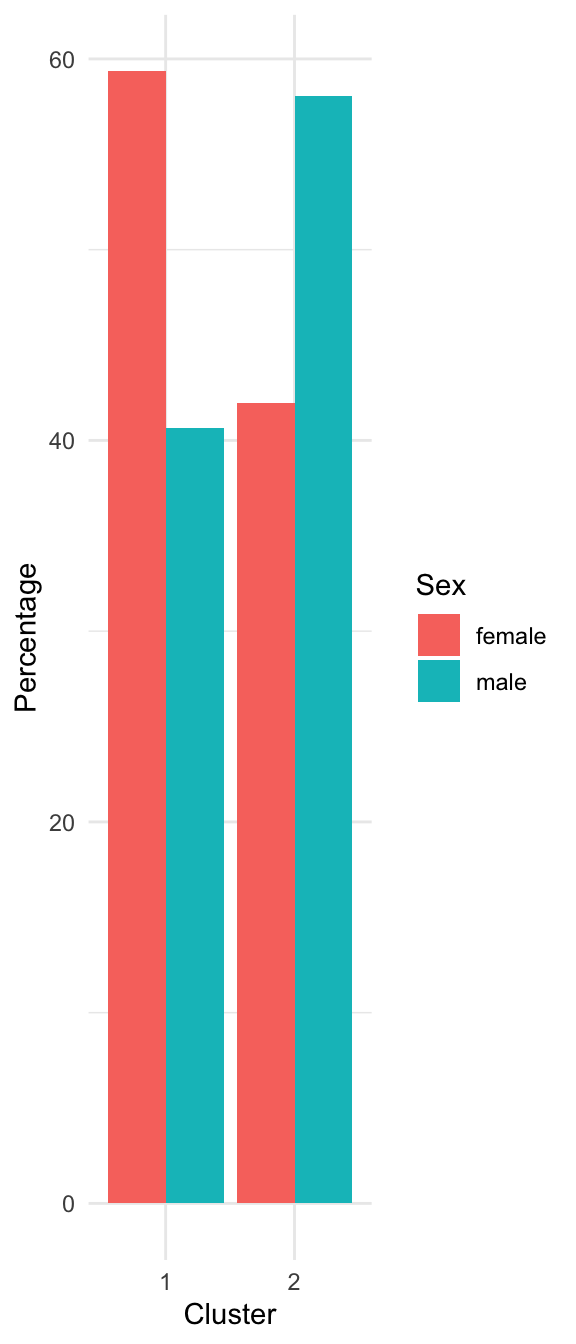

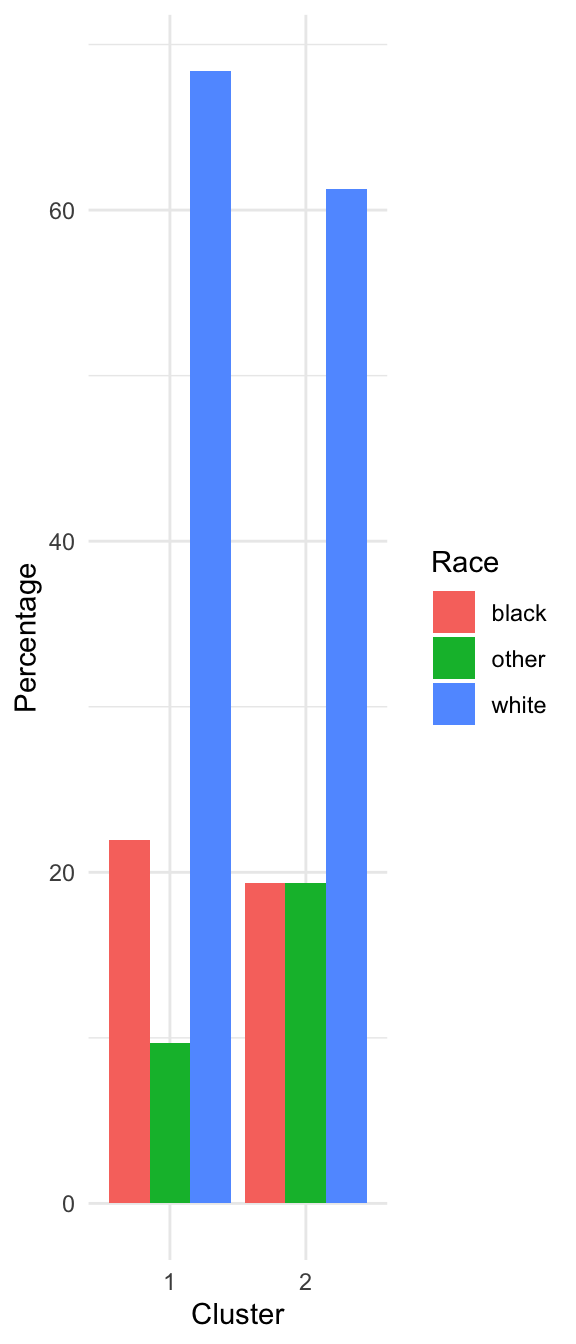

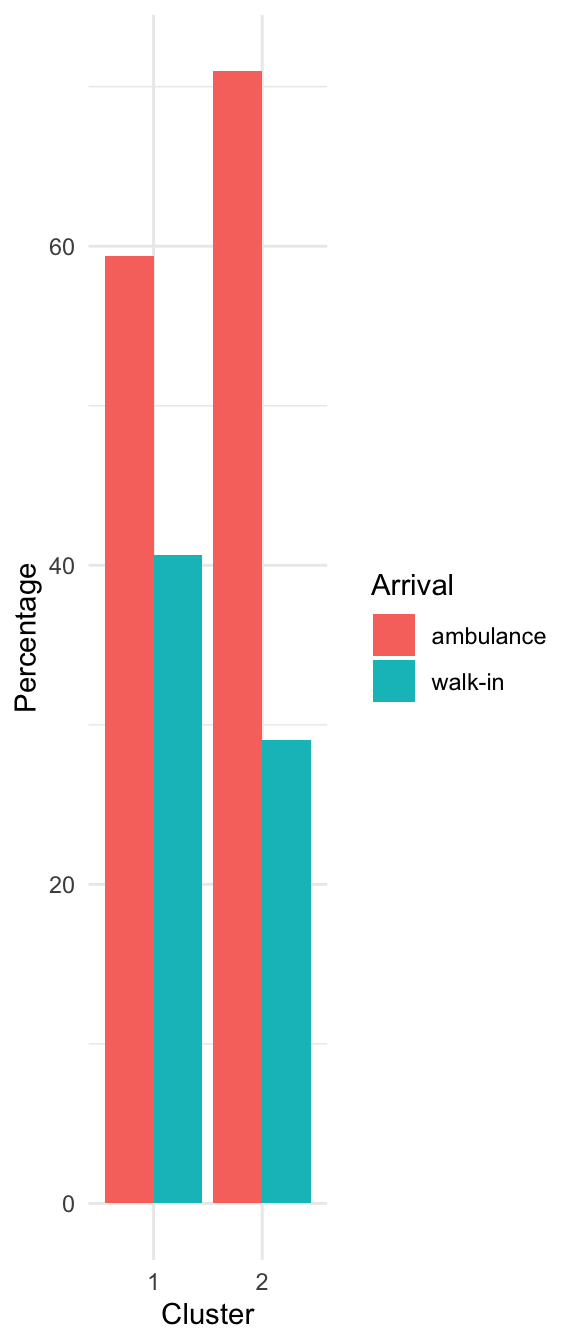

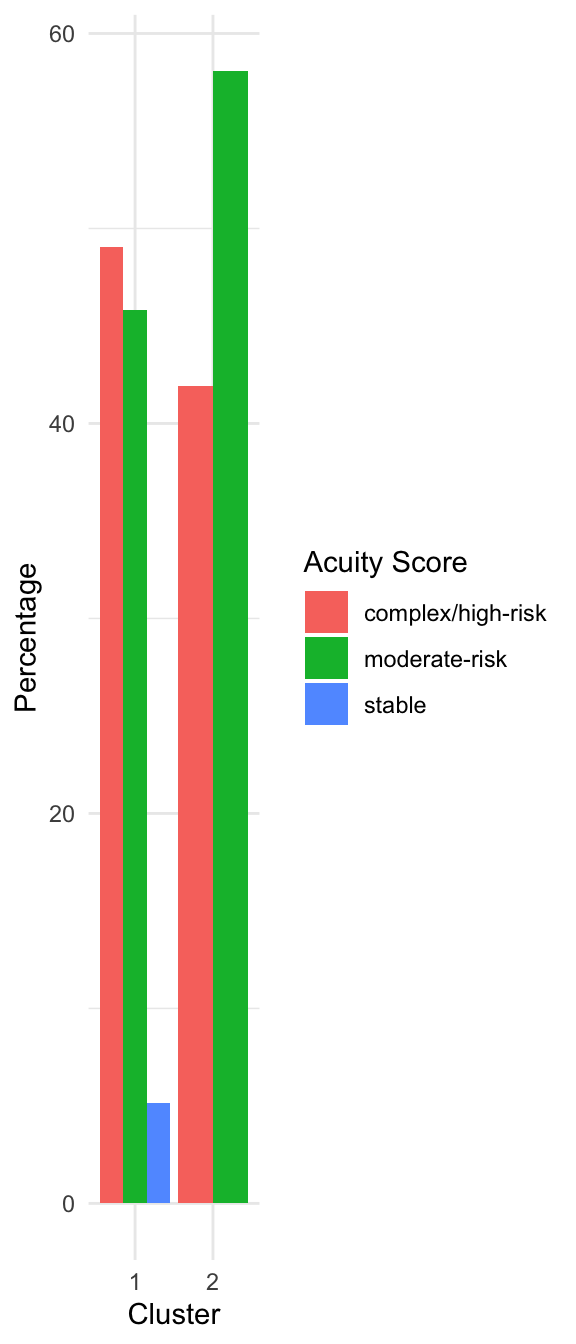

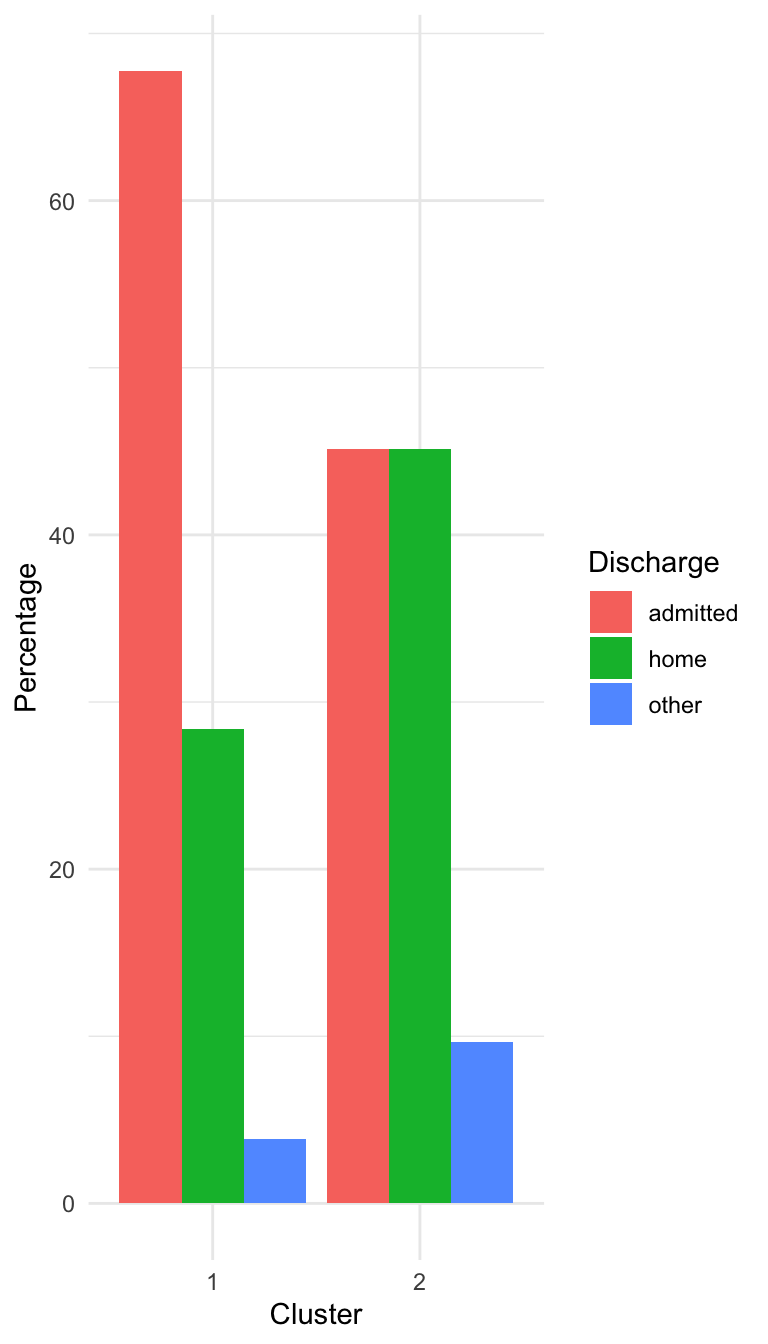

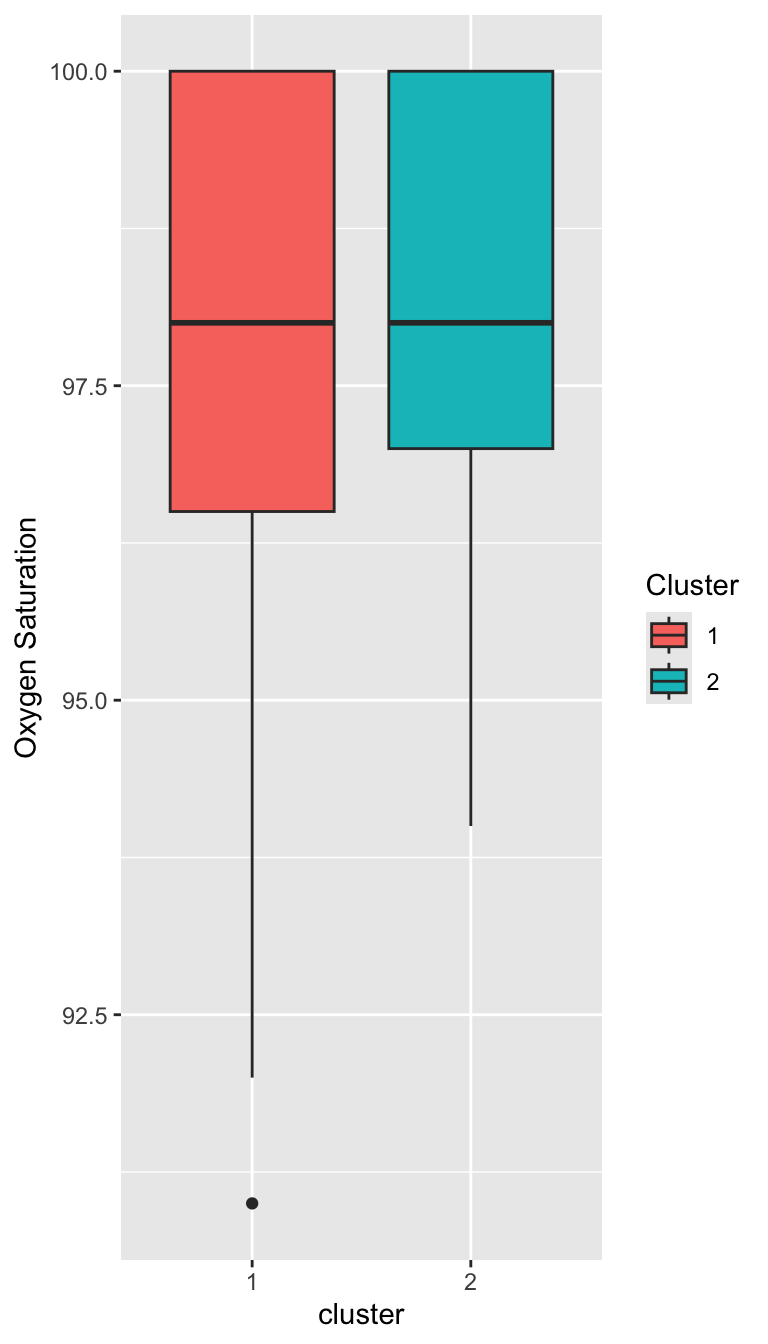

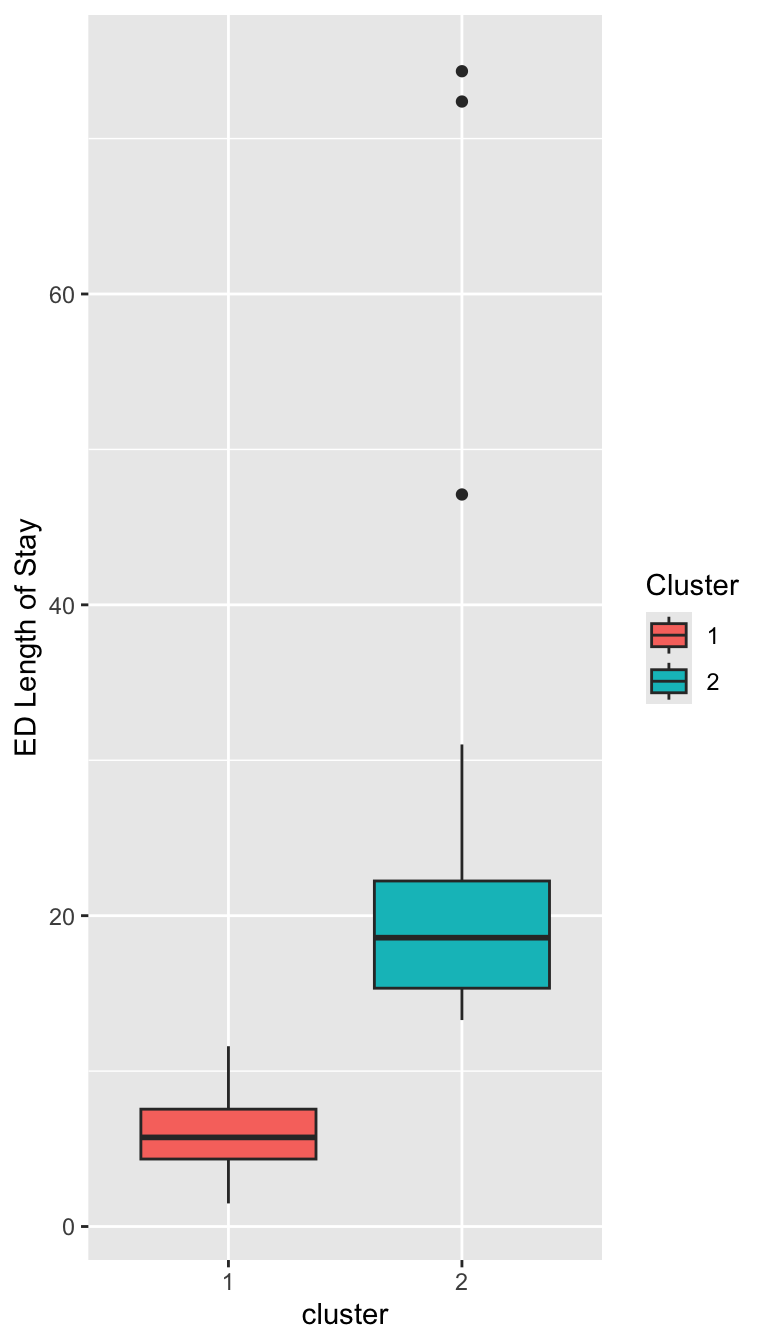

Characterizing the Clusters

Characterizing the Clusters

Prepare for next class

Reminder: On Thursday, we will have a in-class live-coding exercise.

Begin working on Exam 02, which is due for feedback on April 15.