Disease Mapping

Mar 25, 2025

Review of last week

Last week, we learned about Gaussian processes.

We learned how to apply Gaussian processes to longitudinal (or time-series) and geospatial data.

Focused on making predictions at new locations across the spatial surface.

Today we will focus on areal spatial data, which has different goals associated with it than point-referenced spatial data.

Lattice Data (Areal Data)

Data observed at the level of an areal unit

- County Level Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Counts

Lattice Data (Areal Data)

- Birmingham Tract Level Poverty Levels

Goals of Areal Spatial Data Analysis

The goal of areal spatial data analysis is to understand how spatial patterns (e.g., mortality rates, disease incidence) vary across different geographic areas (e.g., counties, neighborhoods).

It helps us identify:

Clusters: Areas with similar characteristics (e.g., high mortality, disease prevalence).

Outliers: Areas that deviate significantly from the overall pattern (e.g., unexpectedly high mortality rates).

Spatial Dependence: Whether values in one area are correlated with values in nearby areas (e.g., neighboring counties with similar health outcomes).

Why We Care About Spatial Patterns

Local Insights: Spatial analysis helps identify local variations in health outcomes that may not be apparent when analyzing data at a higher (e.g., state or national) level.

Targeted Interventions: Understanding spatial patterns allows for targeted public health interventions tailored to regions that need attention (e.g., areas with unusually high mortality rates).

Identifying Spatial Clusters: By recognizing clusters of high or low rates, we can investigate potential common causes (e.g., environmental factors, access to healthcare, socioeconomic conditions).

Motivating Data

Today, we will motivate areal spatial data analysis and disease mapping by studying 2020 COVID mortality at the county-level in North Carolina. The data object covid_nc_2020 is an sf object.

Variables are:

name: county name.population: 2020 population.obs_deaths: observed number of COVID-related deaths in 2020.est_deaths: estimated number of COVID-related deaths in 2020.smr: standardized mortality ratio.age: precentage of residents over 60 years of age.poverty: percentage of residents below the poverty line.geometry: contains centroid and boundary information for each county.

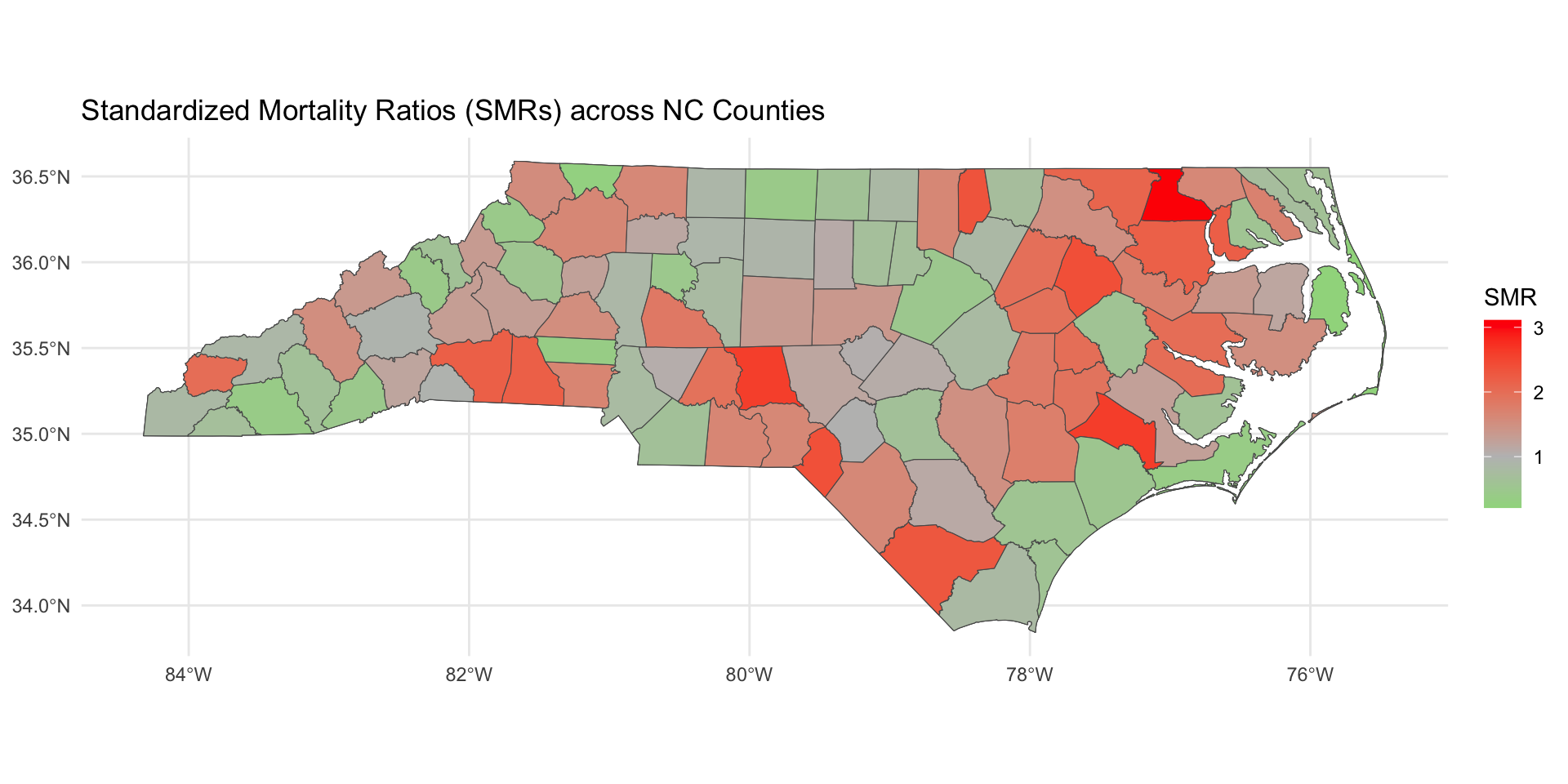

COVID Mortality

Introduction to Disease Mapping

Disease mapping is a way of visualizing and analyzing geographic variations in health outcomes, such as mortality or disease incidence, across different regions (e.g., counties or neighborhoods).

It helps us identify regions with unusually high or low health outcomes, which could be indicative of underlying health disparities.

The Challenge with Observed Data

Imagine you want to compare the number of deaths across counties in a state, like North Carolina. If we simply look at observed death counts, we might be misled:

Larger counties with more people may have more deaths simply due to their larger population.

Smaller counties may appear “healthier” simply because they have fewer people, not because they have lower mortality rates.

Thus, observed death counts are not enough to draw meaningful comparisons.

The Challenge with Observed Data

To make fair comparisons between regions of different sizes, we need to adjust for population size (and sometimes demographics).

Without these adjustments, it’s hard to determine if a county’s high death count is due to its population size or if there’s something unique about the county (e.g., healthcare access, environmental factors) that increases the risk of mortality.

This is where we need more nuanced measures to adjust for population size and allow for better comparisons.

Today we will talk about the standardized mortality ratio (SMR).

Standardized Mortality Ratio

SMR is a way of comparing the observed number of deaths in a population to the number of deaths we would expect, given the population’s characteristics (such as population size).

It adjusts for differences in population, allowing us to identify areas where deaths are higher or lower than we would expect.

- Expected Deaths is calculated by multiplying the total deaths across the state by the proportion of the population in that county.

Example Data

| County | Observed Deaths | Population | Population Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| County A | 10 | 30,000 | 0.3 |

| County B | 15 | 50,000 | 0.5 |

| County C | 5 | 20,000 | 0.2 |

| Total | 30 | 100,000 | 1.0 |

Step 1 - Calculate Expected Deaths

The Expected Deaths for each county are calculated by multiplying the total deaths by the population proportion for that county:

Step 2 - Compute SMR

Now, we calculate the SMR by dividing the observed deaths by the expected deaths:

What do these numbers mean?

Interpreting SMR

SMR = 1: The observed number of deaths matches the expected number of deaths.

SMR > 1: More deaths than expected (excess mortality).

SMR < 1: Fewer deaths than expected (lower mortality).

In our example:

County A has excess mortality, with SMR of 1.11.

County B has as many deaths as expected, with SMR of 1.

County C has fewer deaths than expected, with SMR of 0.83.

Why Use SMR in Disease Mapping?

SMR allows us to:

Make meaningful comparisons across counties of different sizes.

Identify areas with excess mortality (SMR > 1) and areas with lower-than-expected mortality (SMR < 1).

In disease mapping, SMR helps us better understand spatial health disparities and identify regions that may need targeted public health interventions.

Standardized Mortality Ratios

Writing down a model for SMR

Define

Recall that for a random variable

We have:

- Under this parameterization

- Under this parameterization

Disease Mapping Model

The parameter

where

Population parameters:

Disease Mapping Model

The parameter

Spatial Error Term:

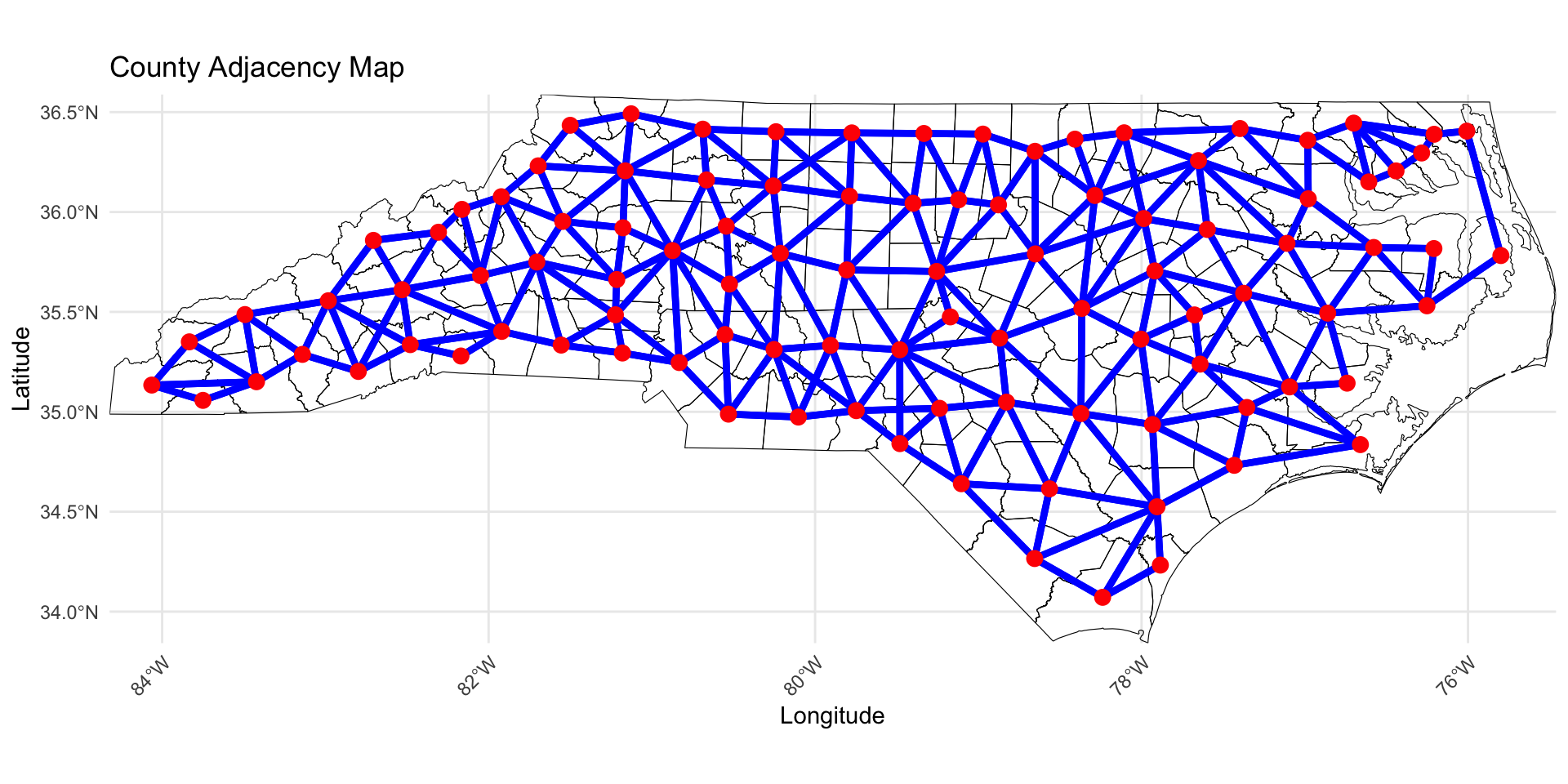

Spatial Correlation: Areal Data

How to induce spatial correlation between areal units?

Distances between centroids (possibly population weighted); may be inappropriate for oddly shaped regions of varying sizes (great for equal sized grid though).

Neighborhood structure of your spatial region; are two regions neighbors?

Correlation introduced through spatial random effects.

The default model for areal data in the Bayesian setting is called the conditionally autoregressive (CAR) model.

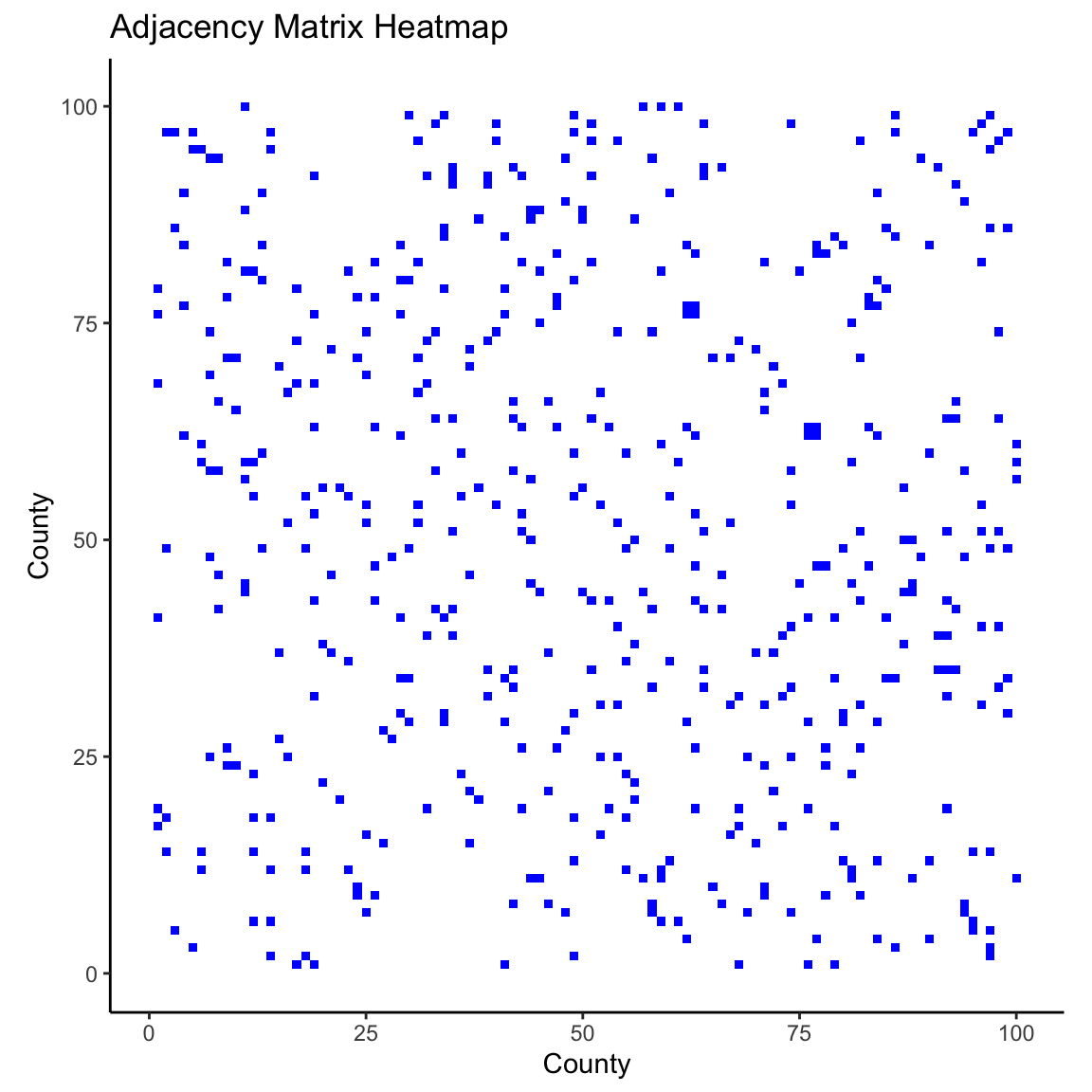

Adjacency Matrix

We will define the matrix

- This is sometimes called a proximity matrix or neighborhood matrix.

Each entry (

In some cases,

Compute Adjacency Matrix

To compute the adjacency matrix of an sf data object we can use the spdep library.

style = "B"specifies binary encoding (1 if neighbors, 0 if not).zero.policy = TRUEensures the function works even if some counties do not have neighbors.

Visualzing the Adjacency Matrix

Visualzing the Adjacency Matrix

ICAR Model

Today, we will look at the intrinsic CAR (ICAR) process for a vector

where

We can still use this as a prior for

ICAR Model: Conditional Distributinos

The joint distribution on the previous slide can be written as a

The mean is an average of the neighbors values.

The variance shrinks as a function of the number of neighbors.

Another Equivalent Specification

Pairwise difference specification:

The impropriety of the distribution can also be seen here, because we can add any constant to all

A constraint such as

We will use this specification in Stan.

Full Disease Mapping Model

The full model can be written as:

where

Posterior Distribution

Define

Adding the ICAR prior to Stan

We will use the pairwise differences specification, so we need the unique pairs of neighbors. We will define

Extracting non-zero edges for Stan

Our goal is to get the row-column pairs from

Since

Adding the ICAR prior to Stan

We can then add the following to the parameters and model Stan code chunks, where we leverage Stan’s ability to perform multi-indexing and vectorization!

Non-centered parameterization

In Stan it is more computationally efficient to use a non-centered parameterization. We define,

We can then recover

Modeling

We specify the following model:

Where

Full Stan Model for ICAR

// saved in icar.stan

data {

int<lower = 1> n;

int<lower = 1> p;

int<lower = 0> n_edges;

array[n_edges] int<lower = 1, upper = n> node1; // node1[i] adjacent to node2[i]

array[n_edges] int<lower = 1, upper = n> node2; // and node1[i] < node2[i]

array[n] int<lower = 0> Y;

vector<lower = 0>[n] E;

matrix[n, p] X;

}

transformed data {

matrix[n, p] X_centered;

row_vector[p] X_bar;

for (i in 1:p) {

X_bar[i] = mean(X[, i]);

X_centered[, i] = X[, i] - X_bar[i];

}

vector[n] logE = log(E);

}

parameters {

real alpha_star;

vector[p] beta;

real<lower = 0> sigma; // precision of heterogeneous effects

real<lower = 0> tau; // precision of spatial effects

vector[n] z1; // spatial effects

vector[n] z2; // heterogeneous effects

}

transformed parameters {

vector[n] theta = tau * z1; // spatial effects

vector[n] epsilon = sigma * z2; // heterogeneous effects

}

model {

Y ~ poisson_log(logE + alpha_star + X_centered * beta + theta + epsilon);

// the following computes the ICAR prior on theta (through the standardized version z1)

target += -0.5 * dot_self(z1[node1] - z1[node2]);

// soft sum-to-zero constraint on theta)

sum(z1) ~ normal(0, 0.001 * n); // equivalent to mean(z1) ~ normal(0, 0.001)

// heterogeneous effects

z2 ~ std_normal();

// population parameters

alpha_star ~ normal(0, 3);

beta ~ normal(0, 3);

sigma ~ normal(0, 3);

tau ~ normal(0, 3);

}

generated quantities {

real alpha = alpha_star - X_bar * beta;

vector[n] log_mu = logE + alpha_star + X_centered * beta + theta + epsilon;

vector[n] lambda = exp(log_mu - logE);

vector[n] mu = exp(log_mu);

vector[n] Y_pred;

vector[n] log_lik;

for (i in 1:n) {

Y_pred[i] = poisson_log_rng(log_mu[i]);

log_lik[i] = poisson_log_lpmf(Y[i] | log_mu[i]);

}

}Fit the Stan Model

X <- model.matrix(~ age + poverty, data = covid_nc_2020)[, -1]

stan_data <- list(

n = nrow(covid_nc_2020),

p = ncol(X),

n_edges = nrow(neighbor_pairs_lower),

node1 = neighbor_pairs_lower[, 1],

node2 = neighbor_pairs_lower[, 2],

Y = covid_nc_2020$obs_deaths,

E = covid_nc_2020$est_deaths,

X = X

)

icar <- stan_model("icar.stan")

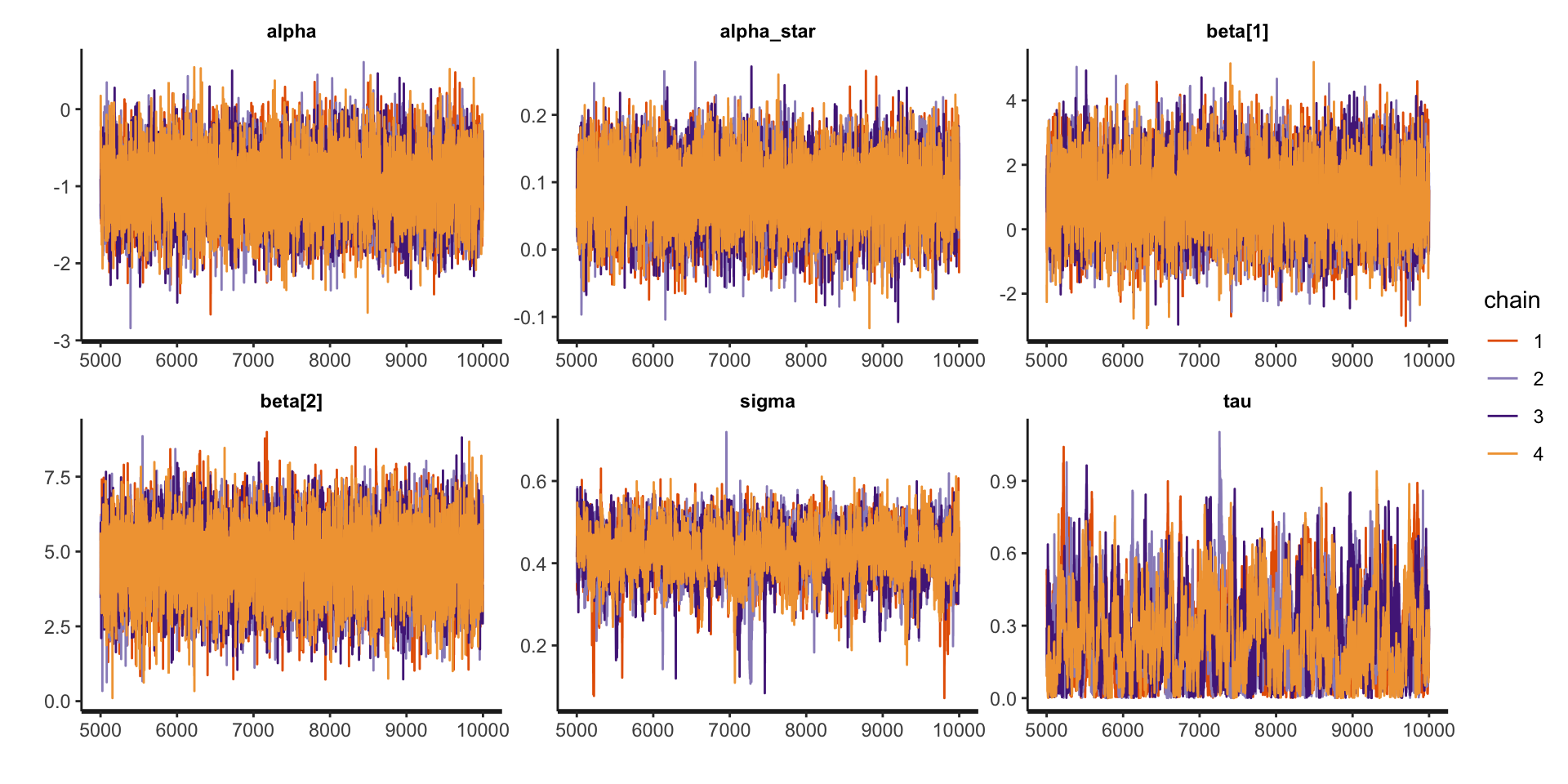

fit_icar <- sampling(icar, stan_data, pars = c("z1", "z2", "epsilon", "log_mu", "lp__"), include = FALSE, iter = 10000)Examine model summaries

Inference for Stan model: anon_model.

4 chains, each with iter=10000; warmup=5000; thin=1;

post-warmup draws per chain=5000, total post-warmup draws=20000.

mean se_mean sd 2.5% 25% 50% 75% 97.5% n_eff Rhat

alpha -0.99 0.01 0.42 -1.81 -1.27 -0.99 -0.71 -0.17 6567 1

alpha_star 0.08 0.00 0.05 -0.01 0.05 0.08 0.12 0.18 6187 1

beta[1] 0.99 0.01 1.05 -1.06 0.28 0.99 1.70 3.06 5966 1

beta[2] 4.66 0.01 1.13 2.40 3.92 4.67 5.43 6.86 6293 1

sigma 0.42 0.00 0.06 0.30 0.39 0.43 0.46 0.53 1087 1

tau 0.25 0.01 0.17 0.01 0.11 0.22 0.36 0.64 550 1

Samples were drawn using NUTS(diag_e) at Fri Mar 21 15:37:56 2025.

For each parameter, n_eff is a crude measure of effective sample size,

and Rhat is the potential scale reduction factor on split chains (at

convergence, Rhat=1).Examine traceplots

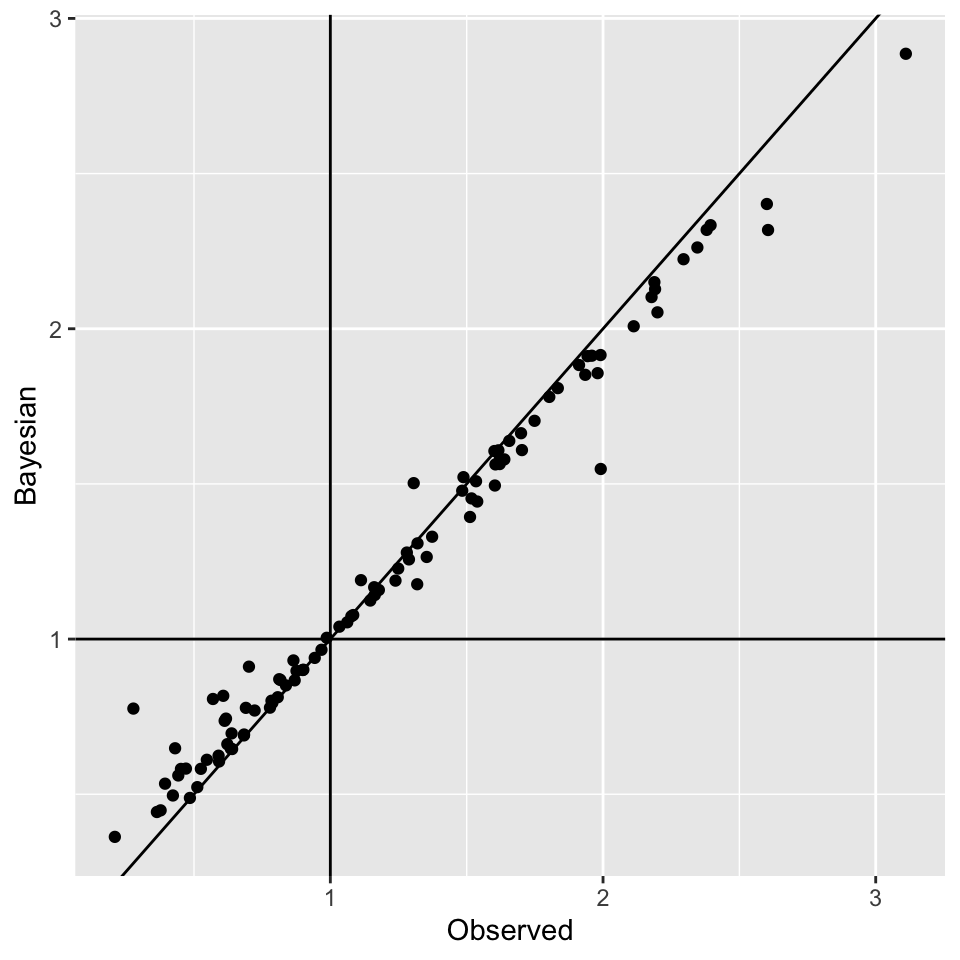

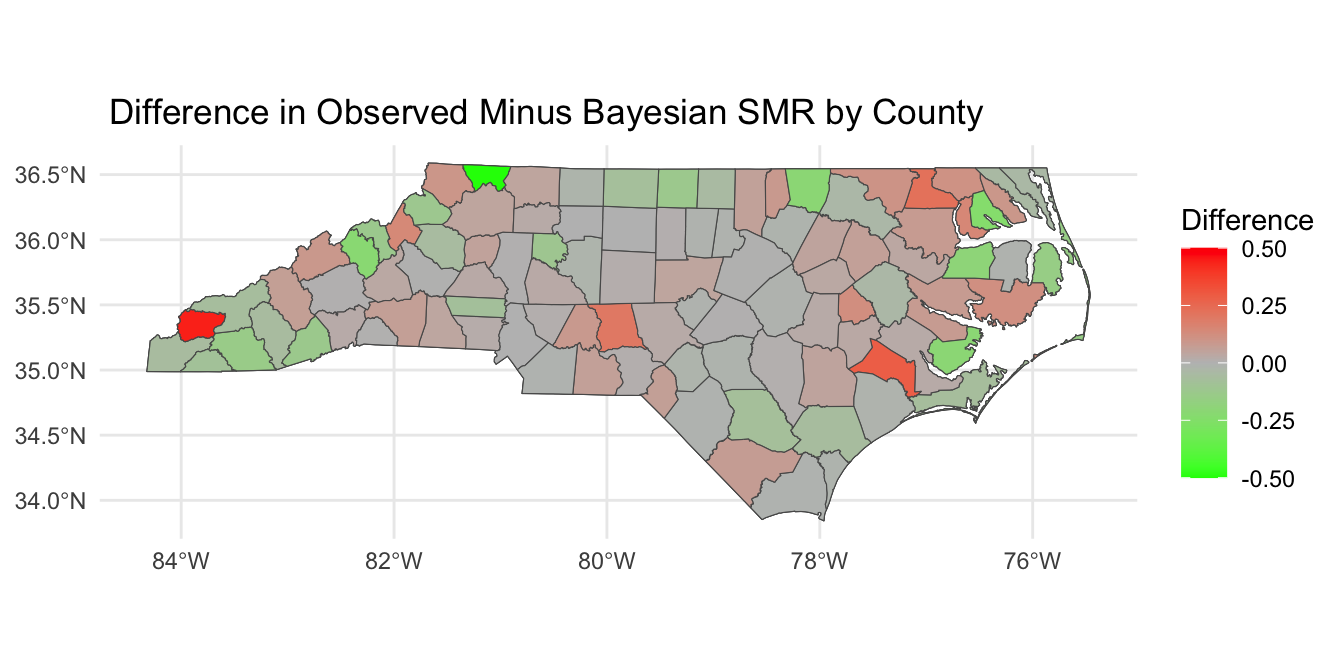

Looking at SMR observed versus

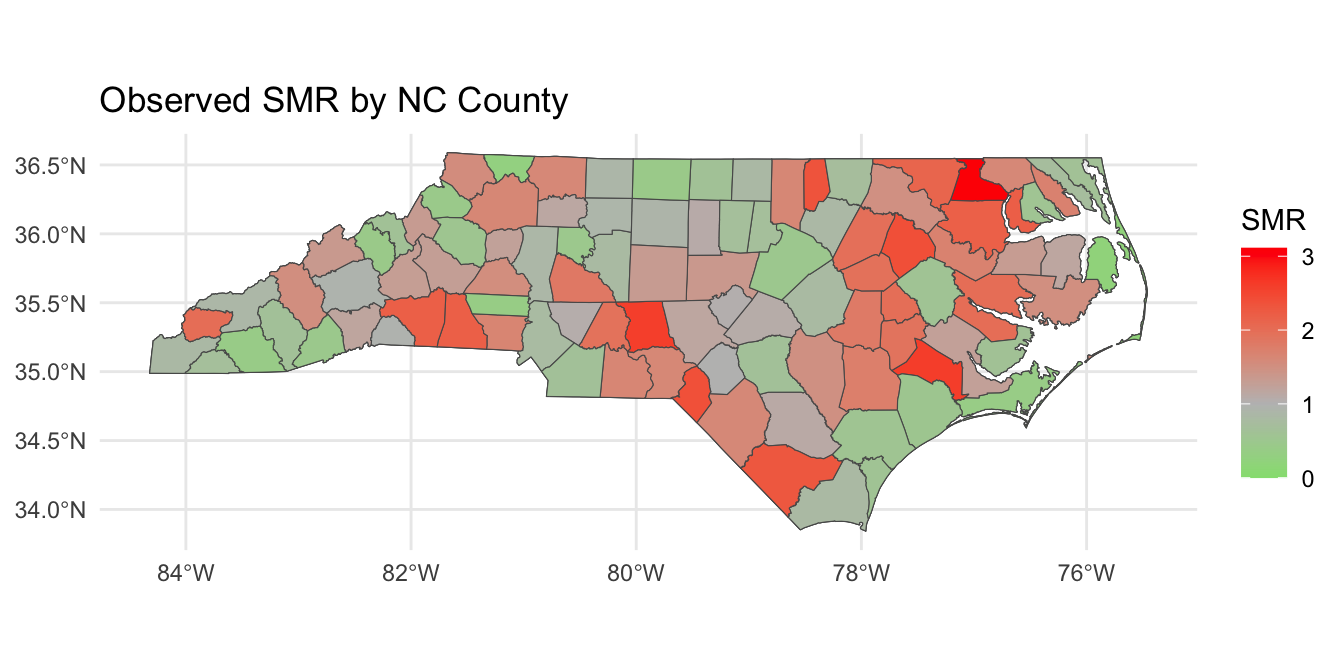

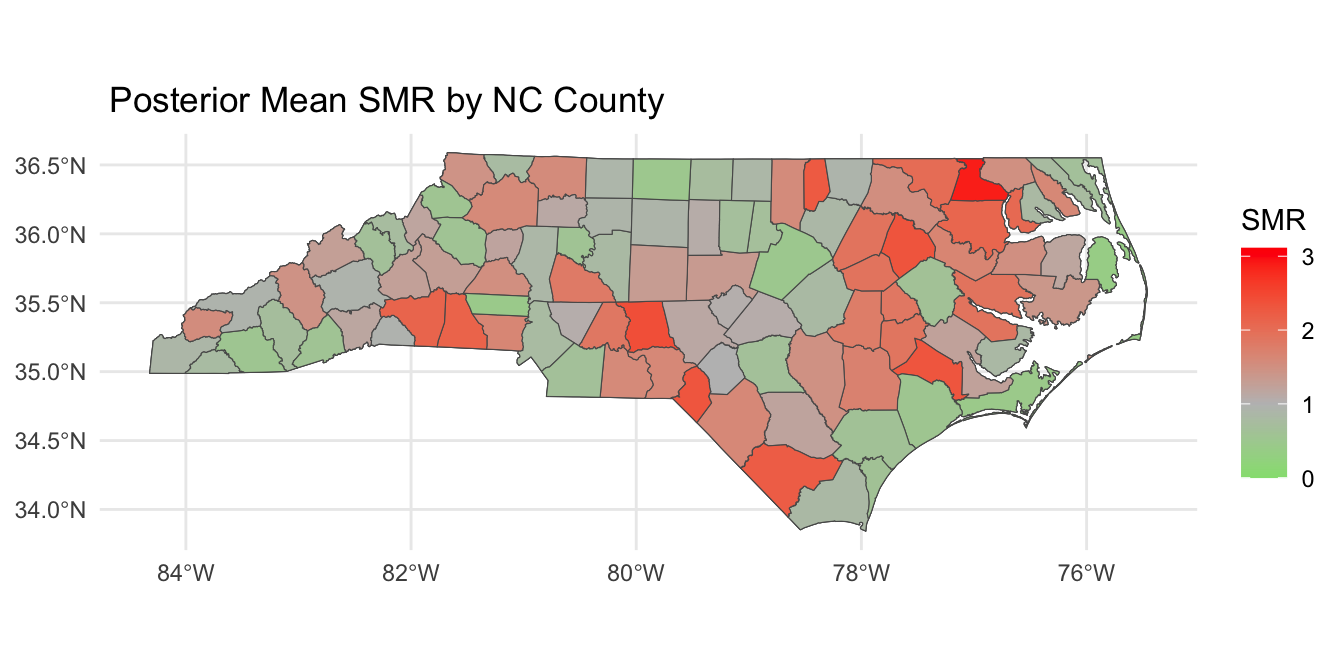

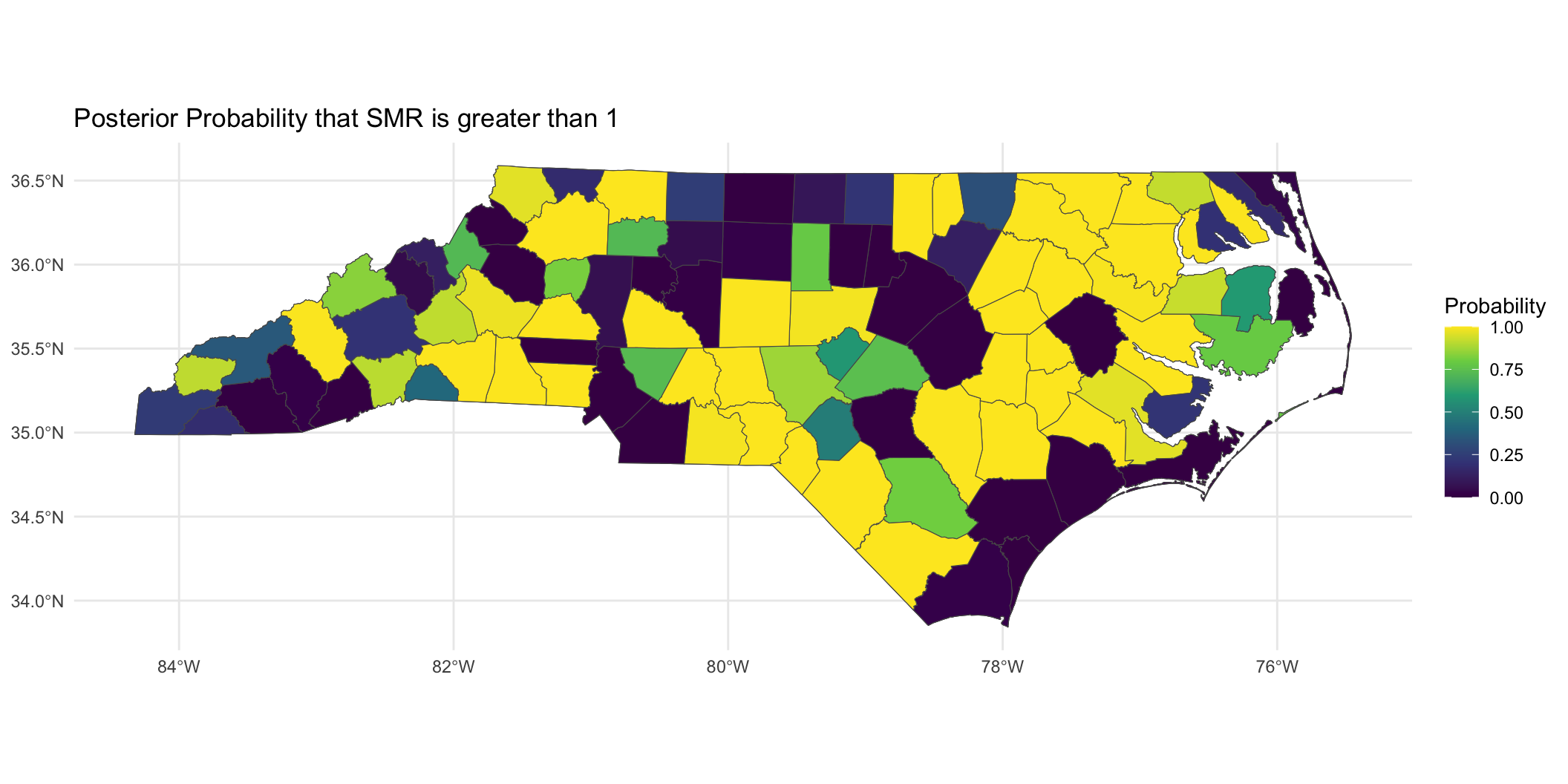

Posterior SMR Across North Carolina

Mapping

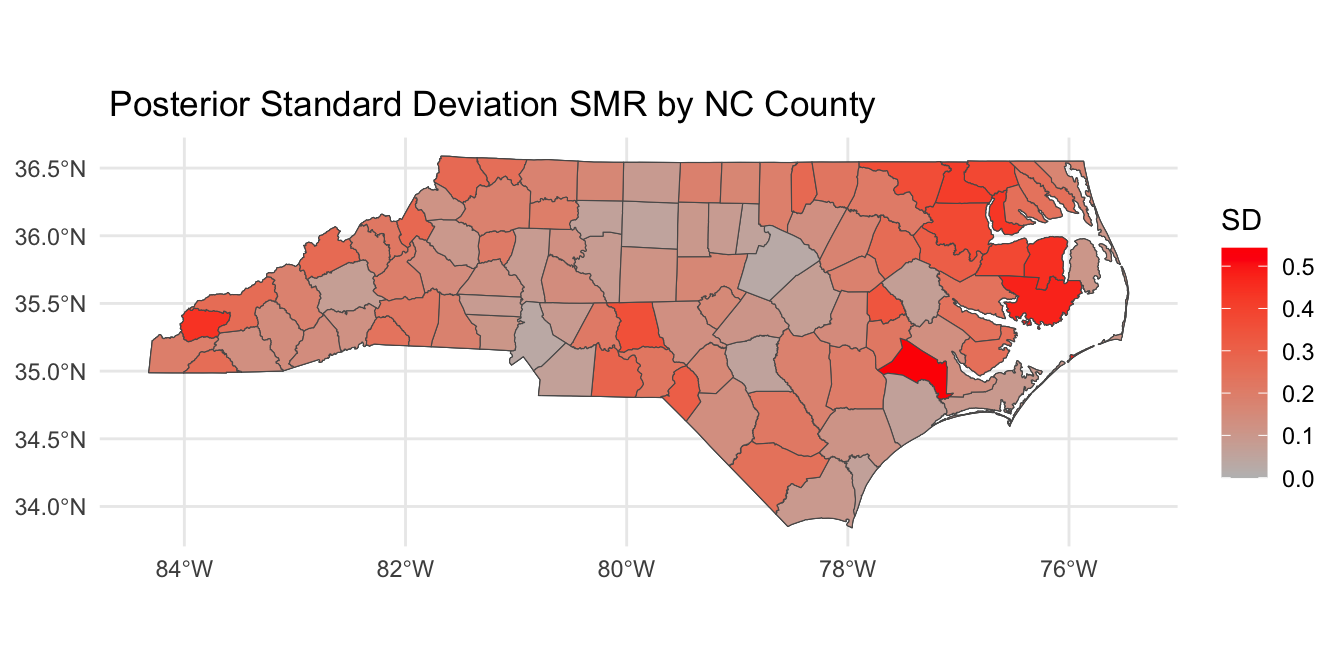

Mapping

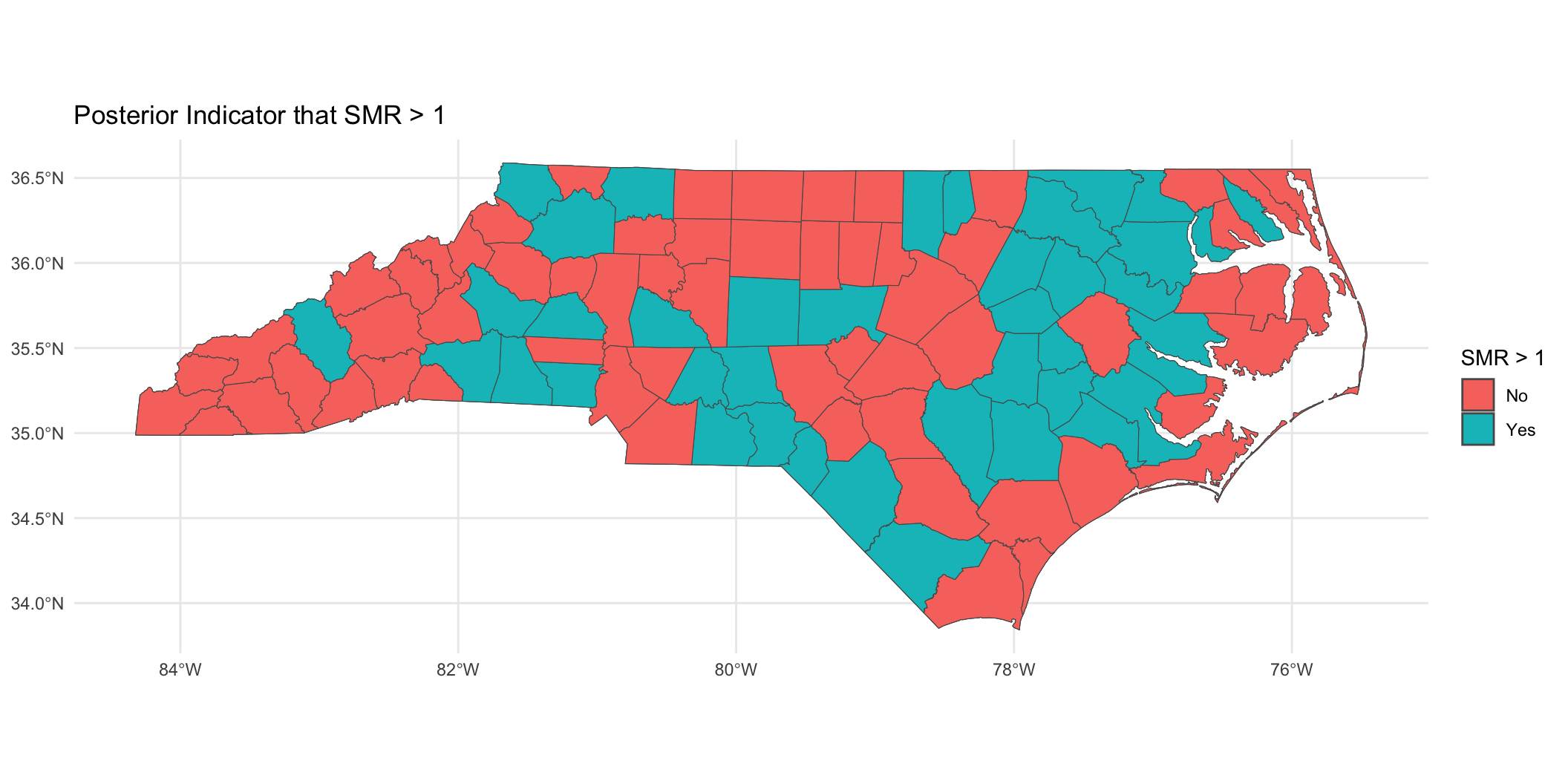

Binary indicator of

Prepare for next class

Work on HW 05, which is due April 8.

Complete reading to prepare for next Thursday’s lecture

Thursday’s lecture: Guest lecture by Prof. Hwanhee Hong on Bayesian Meta-Analysis